Brett Suma left Knight-Swift to work on answering the question, “How do we shape the future of truckload transportation? And how do we shape the future of work in the trucking industry?”

Suma has spent much of his career in trucking working on improving asset utilization and driver satisfaction. He believed there was a better way, using “transformative technology,” to address both issues.

On top of the relatively recent ability to have full asset connectivity and visibility, he was looking at the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning, and autonomous-truck technology on the horizon.

So Suma founded Loadsmith, which started out as a freight brokerage — but the goal is to become much more than that.

To be ready for fully autonomous trucks, he says, “We've got to get to work today to build the most intelligently designed network of freight that we possibly can, that incorporates asset connectivity and visibility. And then we have to deploy trailers in that network so that they flow. And then, once the regulatory and technology environments come together on the autonomous middle mile, we take that technology and we slam it right on top of intelligently designed [freight networks].”

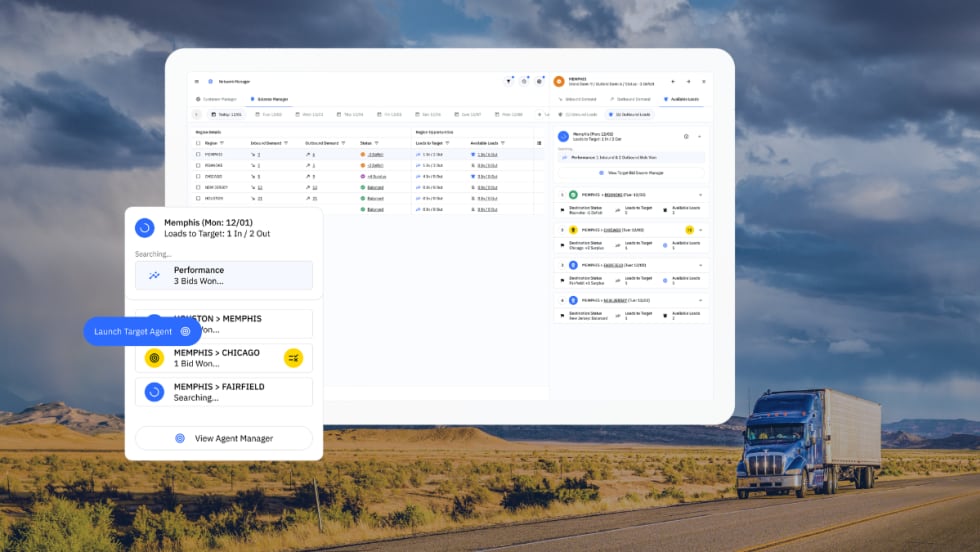

He’s been working on building those smart networks to optimize his current third-party logistics business — or as he describes it, a Capacity-as-a-Service logistics platform for shippers and carriers. The Loadsmith Freight Network allows small and mid-size carriers to scale their customer reach without making a significant capital investment, enabling them to take on high-volume lanes they otherwise would not be able to tap into.

The next step? Deploying autonomous trucks in the middle mile of that freight network, starting in 2025. Loadsmith recently announced plans to equip 800 trucks with Kodiak’s self-driving technology, the Kodiak Driver.

In fact, Suma says, what he’s really doing at Loadsmith is building the first-ever freight transportation company built specifically for self-driving trucks.

Automating the Middle Mile

Most discussions about the commercialization of autonomous trucks revolve around a “hub-to-hub” model, and that's how Suma envisions it, as well.

The Kodiak-equipped trucks on the Loadsmith Freight Network will transport goods autonomously on the interstate portions of highway routes, aka the "middle mile." Human-driven trucks, booked on Loadsmith’s platform, will handle the local pickups and deliveries on either end.

By pairing autonomous long-haul trucks with local drivers that will rendezvous at hubs along and within the LFN, Loadsmith and Kodiak say they’ll enable shippers to move freight more efficiently, reliably, and safely. And this model will allow shippers to leverage autonomous trucks for the long-haul lanes that are less desirable to many drivers.

When looking at the commercial viability of autonomous trucking technology, where they are deployed is going to be critical. Not all lanes are economically viable for autonomous truck operations, Suma says. There needs to be a high volume of freight traffic in a lane to make the math work.

That's why the Loadsmith Freight Network is designed for deployment of autonomous trucks, which will be a subset of lanes that are heavily dense and where the economics of the lane work for this model.

“What we do at Loadsmith is obsessively focus on the most dense lanes in the United States from a freight perspective, and continue to build density either through freight or trucking capacity, so that we're running as many trucks as we can repetitively in between two origin and destination points,” Suma explains.

“Right now, I think there’s a lot of testing going on in lanes that aren’t necessarily best for economic deployment. But from a regulatory perspective, you have to do testing somewhere. As time goes on, I think you’ll see a natural move away from the testing lanes as actual commercially viable.”

Ability to Scale Means On-Demand Freight Capacity

Scale is another important facet of this model.

“While autonomous is not going to solve all segments of U.S. trucking, it can solve a significant amount of the repetitive lanes that exist,” Suma says. “If you can do those in an autonomous way, you’re going to drive down overall transportation costs for shippers because you’ll have on-demand capacity.”

By pairing self-driving trucks and local manually driven trucks on the same network, Suma says, Loadsmith can rapidly scale autonomous deliveries. Once a high-density lane is mapped, he explains, adding capacity can be as simple as having another truck delivered.

How Loadsmith's Autonomous Middle Mile Model Benefits the Truck Driver

Suma says the number one reason he is doing this is the driver. He worked with drivers at his previous job as a Knight-Swift executive.

“What we're trying to build at Loadsmith is the future of work in trucking, the future of the driving job, and deploying technology to make that happen,” he says.

“When you look at the future of work and of workers related around driving, there’s a shortage of really great jobs,” he explains. “When you hear driver shortage, it’s not a shortage of willing participants; it’s a shortage of the work they would be willing to do.”

Using autonomous trucks for the interstate portion of a load give the drivers on either end a local job where they can be home every night.

Stable Rates, Stable Jobs

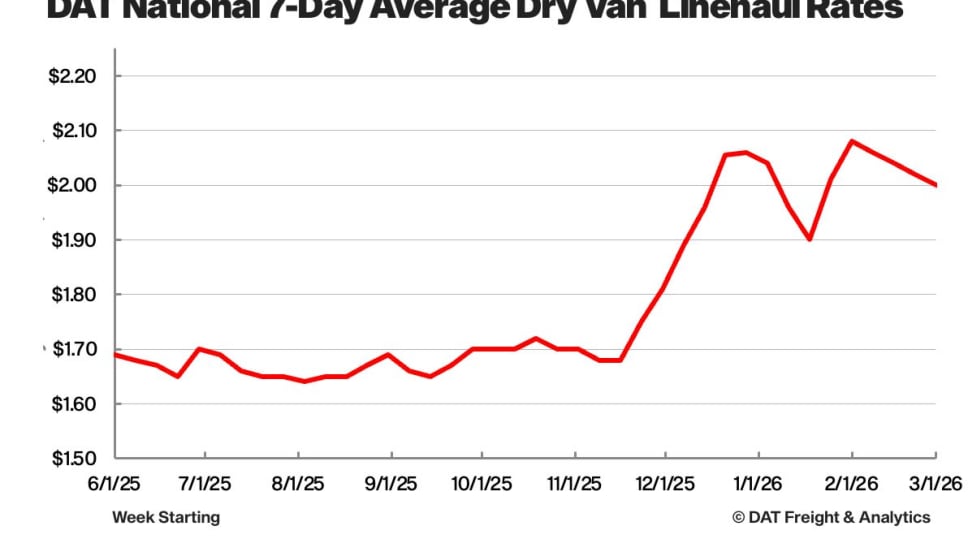

Because of the modular way Loadsmith will do its pricing, the company will be able to offer shippers three- or five-year contract pricing, freeing shippers from the vagaries of the spot market.

That also means this model would allow multi-year contractual agreements with regional trucking companies to do local delivery, meaning more stability for the drivers who work for those companies.

“This will be the force multiplier in great driving jobs, stable driving jobs, and give people the ability to be present in their life away from the truck," Suma says.

He believes this also will help address concerns from labor groups about autonomous trucking decimating driver jobs.

“You have the Teamsters saying autonomous is bad for truck drivers, but when we explain that it’s going to be a multiplier for first and last mile jobs that are hourly, better jobs,” he believes they will change their minds.

Currently, truck driver pay is often not as good for some of those local-type jobs as it is for drivers willing to deal with the sacrifices involved in long-haul. But Suma says the efficiencies of an autonomous middle mile can address that.

“Most drivers don't want to have to make the sacrifices of being gone for weeks at a time, but they do it because that that is where the money is to be made in trucking," he says. "Well, the reason that money is to be made in trucking in there is because there’s a supply and demand inequity over that job. There's really never been a supply and demand inequity on local jobs because there's tons of drivers who want to do those jobs.

“How you can afford to pay them more is by creating higher demand for those drivers by creating more first-mile driving opportunities, but then also driving down the cost of the middle mile so that you can use what you're paying in the middle mile on either end on the pickup and delivery.”

Because that autonomous middle mile will mean high utilization and lower overall operating costs than a human driver, he believes, carriers can push those savings into paying the drivers in the first and final mile better.

The Importance of Trailers in an Autonomous Freight Network

Of course, this model will require a large trailer pool — and that those trailers be kept in tip-top shape.

Loadsmith’s proprietary logistics platform will strategically deploy 6,000 trailers on the LFN to maximize the utilization of the Kodiak-powered trucks on the network.

Suma is using Wabash’s Trailer as a Service offering, having signed a multi-year agreement to add new Loadsmith-branded Wabash DuraPlate dry van trailers into service over the coming years.

The added capacity through the Wabash TaaS platform allows Loadsmith to scale its offering to meet the needs of any size customer, engage with more shippers and deliver consistent freight for carriers through a simple, easy-to-use platform.

Loadsmith’s proprietary logistics platform will strategically deploy 6,000 trailers on the LFN to maximize the utilization of the Kodiak-powered trucks on the network.

Photo: Loadsmith

“One of the things we have to build into our proprietary app and carrier portal is an enhanced trailer inspection so each trailer is being inspected at a very high level," Suma says. "We benefit from the fact that all our trailers are brand new. You’re taking the latest and greatest technology [in autonomous trucks], and you can’t put a 12-year-old trailer behind that.”

Because what happens if the trailer breaks down, or there’s an accident caused by a mechanical component on the trailer? Where does the motoring public lay the blame?

“One of the things we have to do is be great at equipment maintenance and inspecting our equipment,” he says. “A lot of things are more complex than perhaps people realize” in commercializing an autonomous-truck model.

Why Kodiak?

Asked why he chose Kodiak to partner with, Suma says, "I feel that Loadsmith is very progressive in what we’re trying to do. Kodiak shares that vision, and they do it in a simple and elegant way. I decided to partner with them because of that and their open mindedness on how a company like Loadsmith can scale from essentially zero trucks to the first autonomous trucking company.”

After having “kicked the tires on all the players in the space,” Suma says, he believes Kodiak has both the technology and the ability to get to market.

“This is a long runway to get to commercialization,” he says. Kodiak has “made some very good decisions,” he says, including the hiring of former USA Truck CEO James Reed, who joined Kodiak Robotics as chief operating officer.

“James and I had never met, and the first time we got into a room together we couldn’t quit talking,” he says. “He understands the trucking aspect of it and the real application for autonomous and how you can scale it faster by not trying to solve for all.”

What it Will Take to Get to Commercialized Autonomous Trucking

Plans are for Kodiak to begin delivering the Kodiak Driver-powered self-driving trucks in the second half of 2025. Suma acknowledges that there’s a lot of work to do for both companies between now and then.

“Kodiak has a lot of work to do to get to the delivery of the truck, but we also have a significant hill to climb,” he says, in determining the network design, which needs to be scalable.

“800 trucks with an average use of 2.5 times the normal truck means the capacity is around 2,000 trucks,” he says. “That would make Loadsmith the 50th largest capacity provider in U.S. overnight. We have a lot of work to do in order to support that level of capacity.”

Loadsmith’s technology will allow it to maximize the utilization of that middle mile autonomous truck, running back and forth between origin and destination. But to do that requires each load being broken into three pieces – the pickup by a human driver, the autonomous middle mile, and the delivery by another human driver. And those drivers need to be able to pick up another loaded trailer once they’ve delivered their trailer to the transfer point where the autonomous truck takes over.

“We’re building a lot in regards to machine learning, how we’re going to take a modular approach to pricing.”

The plan is to be able to offer shippers three- or five-year contract pricing, “which is unheard of in the industry,” Suma says. “The ability to scale, to handle all the volatility for the customers, and the ability for us to say we can accept 100% of the freight [in a lane] without regard to market fluctuations, to capacity fluctuations. The customer no longer has to worry about the spot market.”

Another key factor in successful deployment, he says, is the real estate aspect.

“This is going to be another area where I think you’ll see entrants into the market,” he says. There have to be facilities designed for autonomous vehicle operation.

“When you think about autonomous middle mile, and the need to break those loads into the first-mile pickup, the autonomous middle mile, and last-mile delivery. It will not work if you’re not able to pair a delivery with a pickup. If I’m a local driver supporting the Loadsmith autonomous middle mile, I’m going to show up to the yard — it might be a Ryder or Pilot or Loadsmith yard — when I leave with my first load to deliver, I’ll pick up at a customer and come back. That’s part of what we’re designing. You’ll have to have fueling, or down the road charging or hydrogen fueling, diagnostic bays, the ability to download and upload into the trucks.”

Addressing the Autonomous Skeptics

“There’s a lot of resistance to this technology, and I think we need to understand why,” Suma says.

While it might sound counterintuitive, Suma says, he believes using autonomous trucks this way “is the right thing to do for the driver, and for future drivers and workers that choose driving as a profession. It’s the right thing to do for shippers providing more stable capacity offering.

“And it’s the right thing to do for the public.” Beyond the safety benefits of autonomous trucks, he says, this kind of network design could mean an easier transition to zero-emissions vehicles, because fueling/charging infrastructure could be installed along these high-density lanes.

“If we can go into a customer for a particular lane and say, ‘We can give you three-year contract pricing,’ that’s a powerful sell — [as is] selling to the driver that you can be home every night.”

“There are skeptics, and I understand that,” Suma says. When he started working on Loadsmith, he did some extensive research into “generational cohorts” and their behavior.

“The values of Millennials and Gen Z are vastly different than Boomers and Gen X,” he says. As an example, he notes, “I’m barely a Gen X, and my dream car is like a V-10 or V-12 sports car. Millennials, the next policymakers, they say a Tesla.

“You have this next generation of decision-makers coming to the forefront and their attitudes toward technology are vastly different. They’ve up with technology embedded in everything they do, and they expect it to be. It’s hard to believe someone using Autopilot in their Tesla would have a problem with the truck next to them also being on autopilot.”

Asked about the reaction of the industry so far, Suma says, it partly depends on what generational cohort the person you’re talking to is in.

“We have carriers that are excited about it, shippers that are excited about it, carriers that don’t want it to happen and shippers that don’t think it will happen. But once the ball is rolling and once Loadsmith’s modular pricing approach comes to fruition and these companies on their OTR freight are able to lock in lanes for three or five with adjustments for inflation only, no spot market, those conversations will change very rapidly.”

Another major catalyst for that change, he thinks, is going to be the move to zero emissions.

“Because of the way you have to build autonomous networks with defined origin and destination points, you can’t have it be more than about 400-450 miles apart,” he explains. “Those will be ripe to convert to zero emissions as well. California, for example, is pushing back on autonomous right now, but I venture to say if someone came to them and said that we can decarbonize Ontario to Stockton, the most dense lane in U.S. but only if we do it with autonomous middle mile, it changes the conversation.”