Navistar, partnering with General Motors and hydrogen fuel-provider OneH2, believes it will have a hydrogen fuel-cell regional Class 8 truck available byMY 2024, with a complete ecosystem that addresses the fueling concerns that have been a stumbling block for the development of fuel-cell electric trucks.

Fuel-Cell Electric Truck ‘Ecosystem’ on the Way from Navistar, GM, OneH2

Navistar, partnering with General Motors and hydrogen fuel-provider OneH2, believes it will have a hydrogen fuel-cell regional Class 8 truck available by MY 2024, with a complete ecosystem that addresses the fueling concerns that have been a stumbling block for the development of fuel-cell electric trucks.

Navistar is working with GM, OneH2 and J.B. Hunt to develop the fuel-cell-electric International RH.

Photo: Navistar

Also part of the team is J.B. Hunt, which will be Navistar’s partner in testing a fuel-cell International RH regional truck in real-world dedicated freight operations.

Navistar said it’s introducing a complete solution, an "ecosystem," for customer implementation of a zero-emission long-haul system.

“Hydrogen fuel cells offer great promise for heavy-duty trucks in applications requiring a higher density of energy, fast refueling and additional range,” said Persio Lisboa, Navistar president and CEO, in a news release.

Navistar plans to have test versions of the International RH Series fuel cell electric vehicle begin the pilot phase at the end of 2022. The company said the integrated solution will offer a target range of 500-plus miles and a hydrogen fueling time of less than 15 minutes.

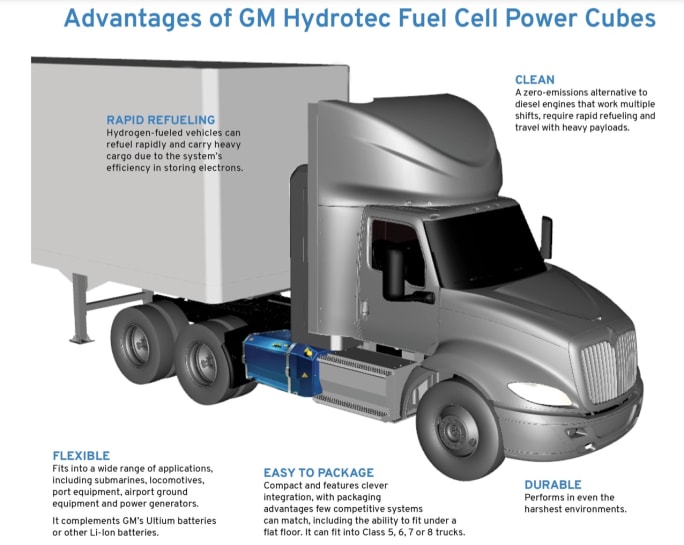

The fuel-cell RH will get its energy from two GM Hydrotec fuel cell power cubes. Each Hydrotec power cube contains 300-plus hydrogen fuel cells, along with thermal and power management systems. They are compact and easy to package into many different applications, GM says.

The combined propulsion system within the International RH Series FCEV will feature better power density for short-range travel, better short-burst kW output, and a per-mile cost expected to be comparable to diesel in certain market segments, according to the company.

GM’s Hydrotec fuel cell technology consists of a stack of fuel cells, with a “plant” wrapped around them to do things such as move the coolant around, inject the hydrogen, and so forth.

“That's a key element of what goes into the power cube,” explained Charlie Freese, executive director of GM’s global fuel cell business, in a call with reporters. “And the power cube then integrates some other parts to bring it to kind of a standardized building block, that you can then put in one, two or three of these into a vehicle with a standardized interface that has power electronics and other things integrated into the control architecture. There will also be things in the vehicle that interface with that, of course, but the idea of power cube is to have a standardized interface.”

GM's Hydrotec fuel-cell "power cubes" are modular in nature.

Photo: Navistar

Technical details about the fuel-cell RH so far are scarce, but Navistar emphasized that it will be working closely with GM in developing the truck. Navistar’s eMobility headquarters in Rochester Hills, Michigan, is only 8 miles from GM’s fuel-cell operations, said Gary Horvat, vice president of Emobility for Navistar. “The basic fuel cell design and integration and development – it’s not just ‘buy something and incorporate it into our vehicle, it’s a true partnership to work together to develop the technology and integrate it.”

Where Will the H2 Come From?

One of the biggest questions that arises when discussing fuel-cell electric trucks is the fueling infrastructure, which presents even more complex problems than the charging infrastructure for battery-electric commercial vehicles.

Navistar believes it has the answer in its partnership with OneH2, which will supply its hydrogen fueling solution. The plan includes hydrogen production, storage, delivery and safety. (Navistar also is taking a minority stake in OneH2.)

OneH2, headquartered in Longview, North Carolina, is a privately held, vertically integrated hydrogen fuel company, combining scalable hydrogen fuel systems coupled with cost-effective delivered hydrogen fuel for use in industrial vehicle and truck markets.

OneH2 has been using a hub-and-spoke model, where central production hubs produce low-cost hydrogen, which is then transported by trailer to refueling locations at industrial centers such as factories, port precincts and warehouses. In 2019, it was selected to supply hydrogen for a fleet of fuel-cell electric trucks to be operated at the Ports of Los Angeles and San Diego as part of the Fast Track Fuel Cell Truck Project.

However, OneH2 also has “invested heavily in miniatured steam methane reforming so we can produce hydrogen in modularized form,” said Paul Dawson, president and CEO of OneH2. “We don’t necessarily need to build a mega-size plant and haul it miles to the customer.”

As a recent North American Council for Freight Efficiency report explained, steam-methane reforming of natural gas is currently the most common way to product hydrogen. It’s known as black or gray hydrogen because of its high-carbon production process as it turns natural gas into hydrogen. It’s possible to sequester or repurpose the carbon emissions, making it a greener alternative (called “blue hydrogen”), but Hobbs noted that comes with extra costs.

By focusing on customers with predictable, dedicated routes, hydrogen fueling facilities will be able to be deployed to support those operations.

Dawson explained that for fleet operations with just a handful of trucks to be fueled at a location, OneH2 can deliver a trailer of hydrogen for truck refueling at a terminal logistics center as it does today in the industrial equipment market.

“One you scale into tens of trucks, the approach is to put a small-scale hydrogen production unit at the distribution center or factory or truck service center.” Or a fleet terminal.

Nick Hobbs, chief operating office for J.B. Hunt, said, “we’ve got over 521 unique locations across the U.S. that we could deploy them to. As we start talking with customers and looking at the application, we have flexibility where it may go.”

Hobbs said it can base anywhere from five to 200 trucks at one of its dedicated customers’ location, so the scalability and flexibility of the OneH2 solution worked out well for J.B. Hunt – and the fast refueling is necessary for the efficiency of the slip-seat operations.

Navistar’s Horvat called “the decentralized method of producing hydrogen that OneH2 brings to the party” an “enabler” of fuel-cell electric trucks becoming a reality.

OneH2 said it will be able to kickstart substantial hydrogen heavy truck refueling infrastructure by turning first to its existing trucking customers, which already are using hydrogen in forklifts, projecting they will be able to incorporate more than 2,000 International RH Series FCEVs into those fleets once production begins.

In the meantime, Navistar said, although J.B. Hunt is the first partner in this endeavor, there will be opportunities for other fleets to acquire and test pre-production vehicles.

The companies declined to say how many of the FCEV trucks would be deployed by J.B. Hunt.

What About Battery-Electric Trucks?

Navistar officials emphasized that they still are developing battery-electric vehicles, as well. Lisboa noted that the company is scheduled to roll its first electric truck off the production line at its new San Antonio, Texas, production facility just over a year from now when it opens in the spring of 2022. (He also said we should start seeing some of those battery-electric trucks this summer.)

“We think both battery-electric and fuel cell technology are important solutions in this marketplace,” said Navistar's Horvat. “Typically lower mileage, 250 to 300 miles or less, would be more battery-electric. As we go father, the fuel cell has an advantage. It really goes on the daily range we want to operate the vehicles at. We’re able to offer products in both of those configurations.”

In addition to range, Persio emphasized that weight and the speed of refueling/recharging mean different zero-emissions vehicles will be better for different applications.

“The challenge for Class 8 trucks is you have to have more batteries for a pure battery-electric truck, and that takes a lot of payload,” he said. “And the charging time is much longer. The fuel cell allowed the truck to go in a higher range and have fast refueling and complete the trip without spending a lot of time in the charging process it would take for a full battery-electric vehicle.”

As for that weight, Horvat said, they anticipate the fuel-cell RH will be heavier than a diesel version but not as heavy as a battery-electric truck would have to be for that application.

Navistar's FCEV will get energy from two GM Hydrotec fuel cell power cubes.

Photo: GM

GM, too, is pushing forward with both battery-electric and fuel-cell electric development. The company recently announced its new BrightDrop business unit, designed to offer electric first-to-last-mile products, software, and services for delivery and logistics companies, along with a new electric delivery vehicle.

Freese declined to discuss its ongoing venture with Nikola during this announcement.

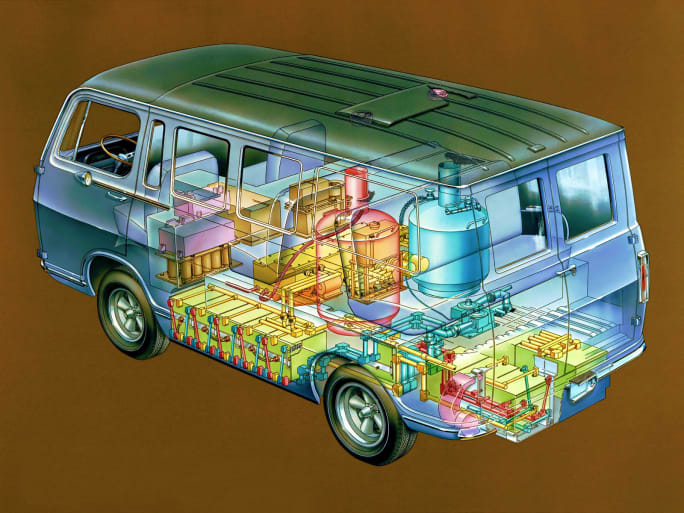

Freese pointed out that the company has been in in the fuel-cell business for well over 50 years. Back in 1966, General Motors tested the Electrovan, the world’s first hydrogen-powered fuel cell vehicle. (Those first fuel cells didn’t allow a lot of room for people or cargo, though.)

General Motors' fuel-cell roots go back to the 1960s.

Photo: GM

So what took so long for fuel cells to become a commercially viable technology for powering trucks?

“The technology evolved through some very substantial breakthroughs,” Freese said. “I’ll be the first to say they have a role to play, but they’re not the only technology that’s necessary. We also need batteries to have a balanced approach. Battery electric is a great tool for certain applications where you’re moving payloads not compromised by the mass of the propulsion system. But if you start to go in and have heavy payloads, so not moving potato chips and half-empty Amazon boxes, but instead moving heavy fluids and things that weigh a lot, that's where you don't want to compromise the vehicle” with that extra battery weight. “We've developed an expertise in both batteries and hydrogen fuel cells, because you do need both technologies.”

Navistar also is forging ahead with other collaborations, including one announced late last year to develop a fuel-cell electric truck with Cummins. When asked about the Cummins project, Navistar spokesman Bre Whalen answered, "To accelerate the adoption of emerging technologies, Navistar believes in collaboration without boundaries, which allows the company to assist customers in developing a zero-emissions business model that reduces carbon footprint in an affordable way, not only a vehicle."

More Fuel Smarts

Run on Less “Messy Middle” Data Shows Multiple Paths for Truck Powertrains [Listen]

Listen as Mike Roeth of the North American Council for Freight Efficiency shares insights into battery-electric trucks, natural gas, biofuels, and clean diesel on this episode of HDT Talks Trucking.

Read More →

Run on Less “Messy Middle” Data Shows Multiple Paths Forward for Truck Powertrains [Watch]

NACFE's Run on Less - Messy Middle project demonstrates the power of data in helping to guide the future of alternative fuels and powertrains for heavy-duty trucks.

Read More →

Trucking Executive Warns Fuel Spike from Middle East Conflict Hitting Fleets Fast

Mike Kucharski, vice president of refrigerated carrier JKC Trucking, says diesel price jumps tied to global instability are squeezing carriers already struggling with weak freight rates.

Read More →

Smarter Maintenance Strategies to Keep Trucks Rolling

In today’s cost-conscious market, fleets are finding new ways to get more value from every truck on the road. See how smarter maintenance strategies can boost uptime, control costs and drive stronger long-term returns.

Read More →

Researchers Demonstrate Wireless Charging of Electric Heavy-Duty Truck at Highway Speeds

Purdue researchers demonstrated a high-power wireless charging system capable of delivering energy to electric heavy-duty trucks at highway speeds, advancing the concept of electrified roadways for freight transportation.

Read More →

EPA Wants to Know: Are DEF De-Rates Really Needed for Diesel Emissions Compliance?

The Environmental Protection Agency is asking diesel engine makers to provide information about diesel exhaust fluid system failures as it considers changes to emissions regulations.

Read More →

Stop Watching Footage, Start Driving Results

6 intelligent dashcam tactics to improve safety and boost ROI

Read More →

California: Clean Truck Check Rules Still in Force for Out-of-State Trucks, Despite EPA Disapproval

The Environmental Protection Agency said California can’t enforce its Heavy-Duty Inspection and Maintenance Regulation, known as Clean Truck Check, on vehicles registered outside the state. But California said it will keep enforcing the rule.

Read More →

Justice Department Pulls Back on Criminal Prosecution of Diesel Emissions Deletes

The Trump administration has announced it will no longer criminally prosecute “diesel delete” cases of truck owners altering emissions systems in violation of EPA regulations. What does that mean for heavy-duty fleets?

Read More →

Why the Cummins X15N Changed the Conversation About Natural Gas Trucking

Natural gas is quietly building a reputation as a clean, affordable, and reliable alternative fuel for long-haul trucks. And Ian MacDonald with Hexagon Agility says the Cummins X15N is a big reason why.

Read More →