The business case for electric trucks is more expensive for fleets than first anticipated, according to Robert Sanchez, Ryder System’s CEO and chairman.

Ryder: Can we Bridge the Cost Parity Gap Between Electric and Diesel Truck Operations?

The business case for electric trucks is more expensive for fleets than first anticipated, says Robert Sanchez, Ryder’s chief executive.

While Ryder expected to see cost increases for adopting BEVs instead of conventional diesel trucks, they did not expect the magnitude of those costs.

Photo: ACT Expo/TRC Companies

Sanchez delivered a sobering keynote address on the third morning of the Advanced Clean Transportation Expo (ACT Expo) in Las Vegas on May 22.

While zero-emission powertrain technologies have made tremendous strides in the past several years, Sanchez maintained that as whole, the technology is still in its infancy. Significant business model issues have been starting to manifest for fleets already deploying battery-electric trucks.

In many respects, Sanchez’s message echoed that of J.B. Hunt President Shelley Simpson the previous day.

BEV Technology is Still in its Infancy

Looking at diesel versus electric in light-, medium- and heavy-duty commercial vehicles, Sanchez said that while Ryder expected to see cost increases for adopting BEVs instead of conventional diesel trucks, they did not expect to see the magnitude of those costs, which he cited as a major barrier to widespread adoption at the current time.

“We know the commercial EVs beyond light-duty transit vans are not ready for mass adoption due to price range and payload limitations,” Sanchez told show attendees.

“We also know that we have a lack of critical charging infrastructure, and we would [have to] make major improvements to their power grid in order to support it.

“From our point of view, for commercial EVs to work in the real world, we need a breakthrough in battery technology and an expansion of the charging infrastructure. We need an inflection point.”

Today's EVs are Like the First Mobile Phones

Sanchez produced a vintage Motorola “brick” cell phone from the podium to make his next point: That BEV technology — much like the brick cell phone in the late 1970s — is still in the very earliest stage of its development path.

Over time, of course, cellphone technology improved exponentially. Better batteries were developed. Phones got smaller. And, as more and more capabilities were added, they eventually evolved into smartphones.

There’s a distinct parallel between the evolution of cellular and commercial zero-emissions vehicle technology, Sanchez said. Like the cell phone, he added, the industry needs electric vehicle costs to come down.

“We need smaller, lighter and more powerful battery technology to improve the range and capacity,” he said. “And we need a nationwide infrastructure. We need the fastest applicable charges available where professional drivers can conveniently charge their trucks.”

We Need a Technological Breakthrough

The North American trucking industry clearly needs a new technological breakthrough to drive capabilities up and costs down. The problem, Sanchez cautioned, is that we don’t know when that breakthrough will come, and what kind of changes it will bring.

The real-world numbers highlight the scope of issue.

“At Ryder, we have a stable of nearly 250,000 commercial vehicles,” he noted. “And only 60 of those trucks are EVs.

“We also have 40,000 commercial vehicle customers. And so far, only 18 of them have chosen to deploy EVs in their fleets.”

Those figures hold true for the North American trucking industry at large, Sanchez added. He said that there are nearly 16 million commercial vehicles in service in North America today. And to date, only 28,000 of them are EVs.

“The problem is not lack of interest,” Sanchez explained. “We have many customers who asked about the cost benefit of converting to EVs. We found that there was significant barrier to conversion in the total cost of transport, or the TCT.”

TCT, he explained, includes the cost of vehicle, fuel or electricity, driver wages, as well as other factors that go into transporting the same load the same distance and achieving the equivalent delivery times.

The business case for converting to BEV technology just isn’t there yet, Sanchez said.

In fact, he added, if you take the average load that is currently being moved by a heavy-duty diesel truck today and convert that tractor to electric, it requires nearly two vehicles and more than two trailers to deliver the same load at the same time as one diesel vehicle, at more than double TCT.

“I think most of you would agree that this is a tough sell.”

The Diesel and Electric Total Cost of Transport Gap

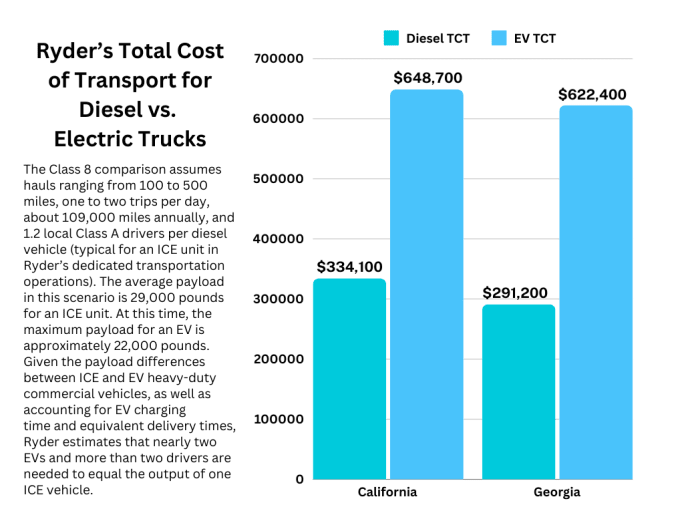

Ryder did the math to better understand how significant the TCT gap between diesel and battery-electric trucks actually is. The results are detailed in a white paper, “Charged Logistics: The cost of electric vehicle conversion for U.S. commercial fleets.”

Ryder analyzed the total cost to transport, in one-to-one comparisons, for transitioning Class 4 (light-duty), Class 6 (medium-duty), and Class 8 (heavy-duty) vehicles operating in California and Georgia from internal combustion engines to EVs in today’s market.

Then it also examined the TCT for transitioning a mixed fleet (light, medium, and heavy) of 25 ICE vehicles to EVs. The mix was based on the overall mix of commercial vehicles in the U.S. according to Polk Data Services.

The analysis is based on representative network loads and routes from Ryder’s dedicated fleet operations, which includes more than 13,000 commercial vehicles and professional drivers, as well as the impact of EV charging time and maximum payload to achieve equivalent delivery times.

Critical factors include general labor, energy costs, loads and routes, Sanchez explained.

“We then factored in a number of cost assumptions using current market prices for vehicles, maintenance, fuel, and charging infrastructure. We also factored in driver’s wages, other professional costs, as well as general and administrative expenses.”

Then, Ryder took the range and payload capabilities needed to achieve equivalent diesel delivery targets and ran the numbers.

“It currently costs about $170,000 a year to run the light-duty diesel Transit van,” Sanchez said. “For electric vehicles, that cost increases an estimated 3%. The cost of the vehicle nearly doubles. However, maintenance cost savings largely offset the increase in vehicle cost.”

The additional driver hours needed for EV charging time in Georgia costs a fleet about $156,000 per year. And while equipment maintenance costs remain the same as that of California, Sanchez noted, Georgia’s lower fuel and energy costs do not provide the same level of savings while transitioning from diesel to electric. All this results in a higher cost disadvantage for Georgia than California.

Heavy-Duty Comparison

As the study moved from light-duty to larger vehicles, the cost benefits start to wane even more.

Looking at Class 8, in Georgia, it costs a fleet about $291,000 to run a diesel-powered truck. In California, it’s about $334,000 per year.

But given current BEV range and payload limitations, Sanchez said it could require nearly twice the equipment and more than twice the labor compared to a diesel truck for fleets to deliver the same loads.

So for that same fleet in Georgia, an electric truck would take $622,438 to deliver the same loads.

In California, the cost to deliver those same loads with electric would cost $648,712.

Overall, Ryder’s analysis estimates cost increases of 94% to 114% to convert heavy-duty trucks to EVs and 56% to 67% to convert mixed fleets of 25 vehicles, depending on which state.

Overall, Ryder’s analysis estimates cost increases of 94% to 114% to convert heavy-duty trucks to EVs.

Image: HDT graphic

Ultimately, consumers will have to pay for those prices increases.

“Keep in mind that nearly three-quarters of all goods in the U.S. are transported by trucks,” he added.

“So if you extrapolate the TCT analysis for the entire U.S. fleet of commercial vehicles to a 100% transition to EVs, and passing the average total cost of transport on to consumers, we estimate that this increased costs cumulatively adding from .5% to 1% in overall inflation.”

Can the Cost Parity Gap Be Closed?

Sanchez said the purpose of Ryder’s analysis is to quantify the current gap in cost between diesel and EVS and to identify the cost drivers.

This, in turn, will help equipment manufacturers, technology companies, innovators, and regulators to better focus their ZEV development efforts.

“We believe those to be advanced battery technology to address payload and range limitations, reducing vehicle costs, and building out sufficient charging networks and delivering power,” Sanchez said. “We believe [by addressing] those three areas … we can start to close the gap and created a cost parity between diesel and electric trucks.”

There are also multiple ways to reduce vehicle emissions, including electric, natural gas, hydrogen, hybrid carbon capture, as well as continuing to advance diesel emissions technology, Sanchez added.

“People and businesses will see the benefits of zero-emission vehicles,” Sanchez said. “And mass adoption will follow. It will take all of us in this room and throughout the industry, working together to strike a balance between encouraging innovation, safeguarding the interests of businesses and consumers and the environment alignment. And I believe this is key for a successful transition to a zero-emissions future.”

More Fuel Smarts

Run on Less “Messy Middle” Data Shows Multiple Paths for Truck Powertrains [Listen]

Listen as Mike Roeth of the North American Council for Freight Efficiency shares insights into battery-electric trucks, natural gas, biofuels, and clean diesel on this episode of HDT Talks Trucking.

Read More →

Run on Less “Messy Middle” Data Shows Multiple Paths Forward for Truck Powertrains [Watch]

NACFE's Run on Less - Messy Middle project demonstrates the power of data in helping to guide the future of alternative fuels and powertrains for heavy-duty trucks.

Read More →

Trucking Executive Warns Fuel Spike from Middle East Conflict Hitting Fleets Fast

Mike Kucharski, vice president of refrigerated carrier JKC Trucking, says diesel price jumps tied to global instability are squeezing carriers already struggling with weak freight rates.

Read More →

Smarter Maintenance Strategies to Keep Trucks Rolling

In today’s cost-conscious market, fleets are finding new ways to get more value from every truck on the road. See how smarter maintenance strategies can boost uptime, control costs and drive stronger long-term returns.

Read More →

Researchers Demonstrate Wireless Charging of Electric Heavy-Duty Truck at Highway Speeds

Purdue researchers demonstrated a high-power wireless charging system capable of delivering energy to electric heavy-duty trucks at highway speeds, advancing the concept of electrified roadways for freight transportation.

Read More →

EPA Wants to Know: Are DEF De-Rates Really Needed for Diesel Emissions Compliance?

The Environmental Protection Agency is asking diesel engine makers to provide information about diesel exhaust fluid system failures as it considers changes to emissions regulations.

Read More →

Stop Watching Footage, Start Driving Results

6 intelligent dashcam tactics to improve safety and boost ROI

Read More →

California: Clean Truck Check Rules Still in Force for Out-of-State Trucks, Despite EPA Disapproval

The Environmental Protection Agency said California can’t enforce its Heavy-Duty Inspection and Maintenance Regulation, known as Clean Truck Check, on vehicles registered outside the state. But California said it will keep enforcing the rule.

Read More →

Justice Department Pulls Back on Criminal Prosecution of Diesel Emissions Deletes

The Trump administration has announced it will no longer criminally prosecute “diesel delete” cases of truck owners altering emissions systems in violation of EPA regulations. What does that mean for heavy-duty fleets?

Read More →

Why the Cummins X15N Changed the Conversation About Natural Gas Trucking

Natural gas is quietly building a reputation as a clean, affordable, and reliable alternative fuel for long-haul trucks. And Ian MacDonald with Hexagon Agility says the Cummins X15N is a big reason why.

Read More →