What are your chances of your trucking company being hit with a nuclear verdict? A bad FMCSA audit? Or skyrocketing insurance rates?

Pretty high if you don't put safety first.

What are your chances of being hit with a nuclear verdict? A bad FMCSA audit? Or skyrocketing insurance rates? Pretty high if your trucking fleet forgets to put safety first. Learn how to build a culture of safety at your company.

Trucking companies that emphasize a safety culture, such as A. Duie Pyle, HDT’s 2021 Safety & Compliance winner, realize benefits such as better insurance rates and increased driver satisfaction.

File Photo: A. Duie Pyle

What are your chances of your trucking company being hit with a nuclear verdict? A bad FMCSA audit? Or skyrocketing insurance rates?

Pretty high if you don't put safety first.

According to the FMCSA, large trucks and buses accounted for 155,585 crashes in 2020, 76,705 injuries, and 4,751 fatalities in 2020. Further, crashes can bankrupt a fleet. The Network of Employers for Traffic Safety (NETS) puts the average cost of a fatal crash at $761,000, with jury awards hitting as high as $1 billion.

Statistics like these drive home the importance of a strong safety culture that rewards good drivers and drives out bad ones.

But what does it take to build a safety culture? Panelists in a recent HDT webinar titled “Building a Safety Culture” defined safety culture and listed how to make it part of day-today operations.

“Every fleet has a safety culture,” says Chris Woody, director of safety for M&W Logistics Group. “The question is: Is it a good safety culture or a bad safety culture? The measure for this leads to another question: What level does safety influence areas of the business?”

Though FMCSA takes safety seriously in the form of regulations, the organization doesn’t define safety culture, according to Attorney Brandon Wiseman, who owns Trucksafe Consulting and is a partner in Childress Law.

The U.S. Department of Transportation, however, defines a safety culture as “shared values, actions and behaviors that show a commitment to safety over competing goals and demands.”

Even with the DOT definition in hand, Wiseman laments all too often the words are “meaningless business speak.”

He adds, “I think it’s critically important, especially in this industry, for carriers to understand what the FMCSA expects in terms of 'safety management control.' That is the term used by FMCSA, the regulator of interstate carriers.”

Wiseman defines safety management control from the regulatory perspective. When the FMCSA audits a motor carrier, its compliance review examines fleet files looking for violations. The auditor then assigns one of three safety ratings to the fleet:

Satisfactory: The fleet has effective safety management controls.

Conditional: Some things are not in compliance. This rating serves as a red flag to customers, creditors and insurers. It can cost fleets customers and increase their insurance and lending rates.

Unsatisfactory: The fleet does not comply with safety protocols. FMCSA gives the operators 60 days to complete a corrective action plan and get it approved to continue operating.

Doug Marcello, an attorney with Marcello & Kivisto, CDLlaw.com, and chief legal officer for Bluewire, sums up a safety culture as, “It’s what you do when no one is watching. It’s about doing the right things all the time, even if it works to your disadvantage.

"It is your corporate reputation, your company integrity. It’s your reputation for doing things that promote safety not just for the company but for everyone on the road.”

A good safety culture is good for business, Wiseman adds.

Too often fleets only see the negatives. He explains when fleets make safety the guiding force in their business, there’s an adverse effect at first.

“Drivers feel they can outwork any regulations that you as a company or the government have about safety,” he says.

A fleet may institute a safety standard about seatbelt use. But drivers may believe the company won’t enforce the policy. They may think, “They are short-staffed. They need me,” Wiseman says.

“You want to stick to your guns,” he adds. “It may have an adverse effect at first and [drivers may leave]. But in the end, you’ll have a group of like-minded drivers who know they work for a company that cares.”

Instituting a safety policy then ignoring it is the worst thing a company can do.

“If you’re going through the motions and just halfway doing it, drivers will spot it right away,” he says.

Wiseman also reminds establishing a safety culture takes time.

“It will not happen overnight. There is no webinar you can watch or safety expert you can bring on to make it happen instantly,” he says.

“You build it brick by brick until it becomes something. Once you get there, you will have an easy time holding onto drivers, and they will refer others to drive for you. And your customers will refer you to other customers. That’s the advantage of doing things the right way.”

Woody echoes this sentiment: “You can make policy in a conference room, but you cannot create safety culture there,” he says.

“It’s got to be something that permeates every part of your business. You’ve got to do it right every single day and build it brick by brick.”

On the flip side, a poor safety culture is bad for business, adds Marcello. Nuclear verdicts — those over $10 million — can put a fleet out of business.

But if a fleet has a strong safety culture, and a “proven history and program of safety, they can defuse a claim for punitive damages,” he says. “If your safety culture is in line, there is nothing there to punish.”

He explains a nuclear verdict requires a detonator, which he defines as “a bad act or something in the safety culture or safety program that sparks a jury.” The detonator paints a case that jurors can protect the community by awarding large damages against the company, he says.

“But if you have developed your safety culture to remove these vulnerabilities, then you have removed the fuel needed for detonation,” he says.

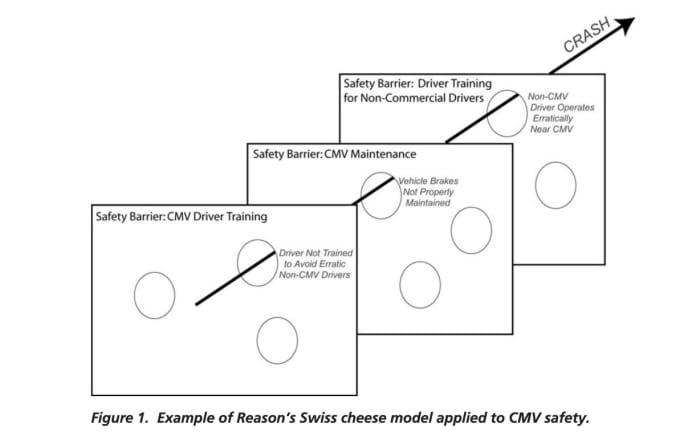

In the Swiss-cheese model of building a safety culture, carriers might choose to determine the current barriers (slices) that are in place, determine the size of the holes or vulnerabilities in each barrier, and determine ways to address those holes.

Photo via FMCSA

Wiseman provides a five-step process to help fleets build a strong safety culture.

Build the Safety Culture. Here, companies must make a safety culture their No. 1 priority and get buy in from the top levels of the organization. “It’s got to be from the top down. And it’s got to be a part of everything,” says Woody.

Develop Safety Policies. Develop and implement strong policies that reflect the company’s safety culture and emphasize compliance with the laws. Create a driver handbook, safety manager policies, drug and alcohol testing policies. “Putting policies in writing says, ‘Safety is our No. 1 priority,” Wiseman says. However, having a policy means little if it gathers dust on a shelf. Wiseman recommends monthly policy reviews and safety meetings to keep everyone on the same page.

Train and Train Often. Safety managers and drivers must be thoroughly oriented and trained on the carrier’s safety policies and regulatory obligations. Training makes sure everyone understands the policies and makes sure “there’s no ambiguity to address,” Wiseman adds.

Auditing. Developing policy and training is not a one-and-done procedure. It’s ongoing. Carriers must periodically audit safety manager and driver compliance with safety policies and regulatory obligations. They do this through annual mock regulatory audits, monthly hours of service audits, etc. “Have very specific auditing processes in place for various issues, whether it be ELD records, driver logs, driver qualification files, drug and alcohol testing records,” he says. “It’s a good practice to audit them and address any gaps before an FMCSA audit.”

Take Corrective Action. When carriers spot non-compliance with safety practices, they must take immediate and forceful remedial action, including retraining on policies and applicable law. “You have got to be ready to stick to your guns on safety,” says Woody. “Are you willing to let your best driver go because he won’t wear a seatbelt? Are you willing to deliver a load late because a driver ran out of hours?”

Make the safety culture top to bottom and in all directions. If only top-level management enforces it, it may not be as effective as if everyone gets involved, Marcello says.

He recalls a company that had an issue with drivers not carrying their med cards and the company’s CSA score kept going up. The company president began allowing all employees to ask drivers for their med cards. If a driver didn’t have one, the company suspended the driver for a first offense and fired him for a second. “They got their point across pretty quickly,” he says.

Don’t hire your problems — only hire good drivers.

“There are three types of drivers: those with impeccable safety records, those with a few things on their records, and those you know will be a problem,” Marcello says.

With the driver shortage, it may be tempting to hire one with a less stellar record. He recommends only hiring the “defensible driver, the driver you want to sit beside in a courtroom if you must defend their actions.”

Wiseman often gets calls from fleet managers who say, “we have these standards in place, but our candidate does not meet one of them.”

Even in those cases, he says not to deviate from the standards. If this driver has a catastrophic accident, your company will need to explain the exception.

“You cannot afford to make exceptions on the standards you have in place,” he says.

Think in terms of how many cents a mile you make on the road. “How many miles will your safe drivers have to drive to pay for that one bad driver or accident,” he says.

Do not overlook internal audits, adds Wiseman. Some carriers perform audits once a year, but if a company does smaller audits throughout the year, they may not need a full-blown audit. Companies also can either perform full audits internally or hire a third party to do it. Mock audits before an FMCSA audit also help. These early examinations identify gaps to fix before an FMCSA audit produces a poor rating.

Add dash cameras to monitor driver behavior, which Marcello says can “keep you from being dragged into a judicial hellhole” when an accident happens. “Cameras are invaluable in these cases,” he says.

A strong safety culture safeguards fleet safety. Investing in safety is also good for business. A robust safety culture keeps trucks safe on the road and gets drivers home safely at night.

Kodiak has integrated HAAS Alert’s Safety Cloud platform into its autonomous vehicle control system to send real-time digital hazard alerts to nearby motorists.

Read More →

Cargo theft has shifted from parking-lot break-ins to organized international schemes using double brokering, phishing, and even spoofing tracking signals. In this HDT Talks Trucking video podcast episode, cargo-theft investigator Scott Cornell explains what’s changed and what fleets need to do now.

Read More →

What fleets need to know about CVSA’s 72-hour inspection blitz and this year’s enforcement priorities.

Read More →

After pushback from states and industry groups, FMCSA is proposing to reverse a 2023 rule change and lengthen the duration of state-issued emergency exemptions for disaster relief.

Read More →

After reports of corrosion and thermal events on trucks already repaired under a prior campaign, DTNA is recalling nearly 27,000 Western Star 47X and 49X models to address a battery junction stud defect.

Read More →

Motor carriers using the affected ELDs must switch to paper logs immediately and install compliant devices by April 14 to avoid out-of-service violations.

Read More →

After a legal pause last fall, FMCSA has finalized its rule limiting non-domiciled commercial driver's licenses. The agency says the change closes a safety gap, and its revised economic analysis suggests workforce effects will be more gradual than first thought.

Read More →

A new AI-powered coaching platform from Samsara uses real-time voice agents and digital avatars to strengthen driver safety and scale fleet training.

Read More →

Geotab launches GO Focus Pro, an AI-powered 360-degree dash cam designed to reduce collisions, prevent fraud, and protect fleets from nuclear verdict risk.

Read More →

A high-visibility enforcement effort conducted January 13–15 removed hundreds of unqualified drivers and unsafe commercial vehicles from major freight corridors nationwide.

Read More →