While some industry pundits have predicted a cliff-event drop in spot rates like we saw in 2018, we are getting increasing anecdotal evidence that what we may instead see is more of a contract rate extended plateau, similar to what we saw in 2011-2012.

Truck Spot Rates Will Mirror 2011-2012 [Commentary]

While some have predicted a cliff-event drop in spot rates like in 2018, there is evidence that we may instead see more of a contract rate extended plateau, similar to what we saw in 2011-2012, Jeff Kauffman suggests.

![Truck Spot Rates Will Mirror 2011-2012 [Commentary]](https://assets.bobitstudios.com/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto,dpr_auto,c_limit,w_920/truck-spot-rates_1768077312731_rx7p9f.jpg)

If the economy grows at about a 5-6% rate this year, and at a 3% rate next year, there is likely to still be support for rate growth in 2022, Kauffman says.

Source: Truckstop.com, FTR

This is an outcome that neither investors nor fleet executives seem to include in their forecasts, as share prices of truckload companies are under pressure in the stock market, despite better than expected first quarter earnings results. But it’s one that is looking more and more likely.

Many individuals tend to see things through the lens of recent experience – in this case, 2018. The last time spot rates crossed the 20% year-over-year increase level and truck orders surpassed 300,000 units, it was followed by a two-year drought in rates and volumes, caused by the industrial recession of 2019 and the Covid recession of 2020.

However, that environment bears little resemblance to the current situation. 2018 marked the end of a three-year period of prosperity and an overbuild of inventory that lost steam in the fall of 2018.

In the current environment, we have yet to cross into positive territory in two key growth metrics – industrial production (still negative) and growth in business inventories (still negative). Rather, given inventory shortages, a modest re-opening of the economy, and ISM (Institute for Supply Management) manufacturing index readings in the 60+ range (implying high future growth expectations), the economy may be at the front end of an 18- to 24-month growth cusp.

Jeff Kauffman

Charting meaningful growth rates will be difficult over the next four to five months, given we are now comparing against last year’s Covid-related global economics closure. Sequential growth analysis may be more helpful. On that basis, using rail carloads as a proxy, we are only recently approaching volume levels that we saw back in January. Rail carloads are clocking +25% year-over-year in the most recent week, but based on our sequential analysis, we are only back to levels where we began the year.

So far this year, three truckload divisions have reported first-quarter earnings (Marten, J.B. Hunt and Knight-Swift). The net capacity increase remains negative. Why so? Although carriers are seeing higher rates now (Knight-Swift reported 16% higher revenue per mile), that has only been the case recently. With extended unemployment benefits delaying new hires, truck driver training schools running at limited capacity, and the national Drug and Alcohol Clearinghouse taking 4,000-5,000 drivers per month out of the truck driver population, growth will be difficult at any reasonable price – no matter how many trucks OEMs produce.

Furthermore, we are hearing anecdotal stories of desperate shippers, unable to effectively use rail or airfreight networks, turning to truck networks to move goods we typically don’t see in longer haul truck routes – scrap metal, pharmaceuticals, and hot-shot cross country moves in lieu of backed-up intermodal. Volumes are increasing, not decreasing. Without additional air cargo capacity or a more fluid rail system with less port congestion, there doesn’t appear to be a catalyst to balance the market in at least the next three to six months.

This leads us to our final point. With limited ability to get goods to where they are going on a timely basis, and new constraints on production of goods related to semiconductor chip shortages, inventories are unlikely to be rebuilt as quickly as originally thought.

In addition, we are beginning to hear increasing anecdotes that shippers may look to try to overbuild product inventory ahead of the holiday and winter season, just in case there’s another healthcare-related slowdown.

When we add all of this up, it implies that the market for trucking capacity is likely to remain tight into the end of the year. If the economy grows at about a 5-6% rate this year, and at a 3% rate next year, there is likely to still be support for rate growth in 2022, resulting in an environment more similar to 2011-2012, where rates were supported for two years past the peak in spot rates.

This commentary originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of Heavy Duty Trucking magazine.

More Equipment

Mack Unveils CommandView Safety and Productivity System for Granite

Mack Trucks’ CommandView is a new suite of integrated onboard technologies designed to enhance jobsite safety, improve operational efficiency for fleet operators.

Read More →

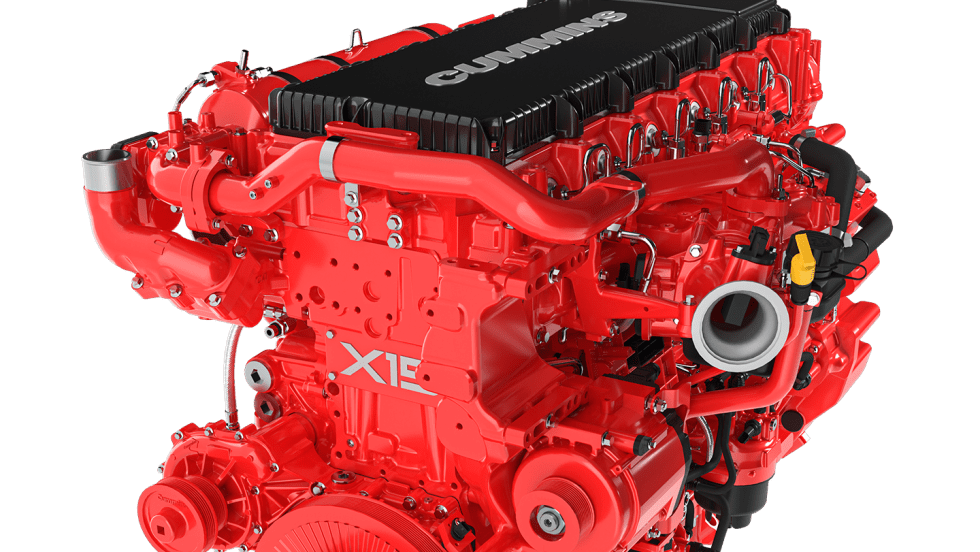

Daimler Adds Cummins Engines to 2027 Powertrain Lineup

Freightliner and Western Star models will offer a broader mix of gasoline, diesel and natural gas engines designed to meet EPA 2027 emissions standards.

Read More →

Smarter Maintenance Strategies to Keep Trucks Rolling

In today’s cost-conscious market, fleets are finding new ways to get more value from every truck on the road. See how smarter maintenance strategies can boost uptime, control costs and drive stronger long-term returns.

Read More →

Peterson to Debut Genesis Fail-Safe Truck and Trailer Light at Major Industry Events

Peterson will debut its new Genesis truck and trailer light at Work Truck Week and TMC.

Read More →

PlusAI Debuts SuperDrive 6.0 With Night Driving, Construction-Zone Capability

The latest version of SuperDrive aims to accelerate path to scalable driverless trucking operations.

Read More →

FTR Reports Class 8 Truck Orders Surged in February

FTR said preliminary Class 8 truck orders jumped 47% month over month and 159% year over year as improving freight conditions and clearer regulatory outlook boost fleet confidence.

Read More →

Kenworth Unveils C580 Extreme-Duty Truck at ConExpo

The new extreme-duty vocational truck replaces the long-running C500 and is designed for the most demanding off-highway applications, with production scheduled to begin in 2027.

Read More →

Mack Debuts All-New Keystone Vocational Tractor, Unveils Reimagined Granite at ConExpo 2026

Mack has debuted an all-new Class 8 tractor and an updated Granite model ahead of ConExpo-Con/Agg 2026.

Read More →

How One Company is Using Smart Suspension Technology to Reduce Driver Injuries and Improve Retention

America’s Service Line adopted Link’s SmartValve and ROI Cabmate systems to address whole-body vibration, repetitive strain, and driver turnover. The trucking fleet is already seeing measurable results.

Read More →

Trailer Orders Hold Steady in January as Backlogs Rebuild

FTR says net trailer orders are flat month over month at 24,206 units, with 2026 orders still trailing last year.

Read More →