A sudden war in crude oil prices between Russia and Saudi Arabia could mean a drop in diesel and gasoline prices at American fuel pumps. But the longer-term implications are more worrying.

Most Americans closed out the first week in March fretting about the onset of COVID19 – the illness caused by the new version of coronavirus that emerged in China late last year – and the resulting stock market crash it triggered as multiple U.S. states reported cases of the virus. Then on Monday morning, March 9, they woke up to discover that Saudi Arabia and Russia were embroiled in a price war centered on crude oil.

HDT turned to a couple of industry analysts for their thoughts on how this trade war flared up and what its implications are likely to be.

Jim Meil, a principle and industry analyst for ACT Research, says there is always tension between oil-producing states, with the countries in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) normally keeping a firm grip on pricing. Saudi Arabia, the world’s leading (and most cost-effective) oil-producing country, is the de facto leader of that group.

Meil noted that oil prices have been slowly eroding for some time now as the global economy has been cooling off – a process that has been expediated by the COVID19 epidemic and the dramatic gains and losses in the stock market.

As oil prices continued to slide, OPEC (read Saudi Arabia) made the decision last week to cut production in order to drive prices back up to around the $55 a barrel mark, which Meil said has been the general price point for the last two-and-half years.

This, however, created a problem for Russia, which is not an OPEC member but is one of the largest producers of crude oil. The Russians and Saudi Arabia have had an alliance in place for some time now to manage oil prices and keep them largely stable and profitable for both countries, as well as for other oil-producing nations.

Russia is struggling under economic sanctions levied by President Obama and Western Europe to punish it for its invasion of Ukraine and subsequent “annexation” of the Crimea. The country is almost wholly dependent on crude oil to keep its already-hobbled economy limping along. Any cut in oil production would have immediate, negative affects on the Russian economy that could worsen an already grim outlook or even lead to unrest – both issues Vladimir Putin's government is keen to avoid.

So the Russians declined to join OPEC’s move to cut oil production. Saudi Arabia essentially replied with, "We’ll cut our prices and you’ll lose money, anyway, until you’re ready to cut a deal with us."

The result was the largest one-day drop in crude oil prices in almost 30 years when markets opened on March 9, adding to the mayhem as shellshocked investors watched stocks fall 1,700 points in the opening round of trading, already primed by increasingly bad news as COVID19 continues to spread in the U.S.

Trading on the New York Stock Exchange was so volatile at the opening bell that a “circuit breaker” kicked in after a 7% drop in the Dow Jones Index, in order to give cooler heads a chance to prevail and heading off a major crash. By the time trading ended on March 9, crude oil prices had nosedived 23% and were trading at $31.84 a barrel.

Low Fuel Prices But Nothing to Haul

So, the Saudis and Russians are fighting and oil prices are dropping as a result. That’s a spot of good news in an otherwise chaotic mess, right?

Well, yes, lower prices at the pump are good news for most trucking fleets. But as Meil and Avery Vise, vice president, trucking research, FTR, pointed out, any short-term gains for the trucking industry in terms of fuel pricing must be tempered with potential longer-term problems, depending on how events play out.

“If we saw crude prices settle in the range where they are trading today – in the low $30 per barrel range – or go lower, we certainly will see further drops in diesel prices,” Vise told HDT. “However, we had already seen a sharp drop in crude prices this year due to coronavirus concerns in January and then the coronavirus-related financial market turmoil that began a couple of weeks ago. The national average diesel prices already has plunged 22 cents a gallon since hitting a six-month high at the beginning of the year. It's not clear, then, how much lower diesel prices will go as a result of Saudi Arabia's actions.”

“The Russians are certainly in a quandary,” Meil said. “They weren’t expecting this level of gamesmanship from the Saudis and seem to have been taken off guard. So it is likely that after a few days, they’ll sit down with the Saudis and hammer out an agreement – say to cut product by about 20%, which has been the Saudi goal since they determined the need to cut production in the first place.”

As for whether or not these moves will be good or bad for North American trucking, Vise and Meil said it all depends on multiple variables.

“If you’re in the long-haul segment, the single biggest determining factor in place are the fuel pricing agreements you have with your shippers,” Meil said. “So, for many carriers, the impact will be minimal, since most fuel price swings are essentially passed through the carriers on both the up- and down-swing in pricing.”

That said, both men note that some fleets will enjoy lower fuel prices for the immediate future. “In the near term, carriers obviously will welcome the relief at the pump, but it's not just an issue of cost,” Vise cautioned. “Rapidly falling prices also boost carriers' cash flow temporarily because fuel surcharge payments based on earlier higher prices are coming in as carriers are paying lower fuel prices. That dynamic stabilizes eventually, but it can help cash-strapped carriers for a month or two. Of course, there's always a risk that the dynamic will reverse, which would hurt cash flow temporarily.”

And, Meil noted, lower fuel prices won’t do much to offset the other negative economic activity swirling around at the moment. “There were signs the global economy was already cooling off before the coronavirus shifted this negative momentum into high gear,” he said. “So – depending on the impact of the virus and how the markets respond, fleets could find themselves in the curious position of having incredibly low diesel prices at the pump, but no cargo to haul with that fuel.”

Effects on U.S. Oil Industry

More worrisome, both Meil and Vise said, is the longer-term affect this new Russia-Saudi price war will have on U.S. oil patch production – which has been a trusty bright spot in the country’s overall economic picture up to now.

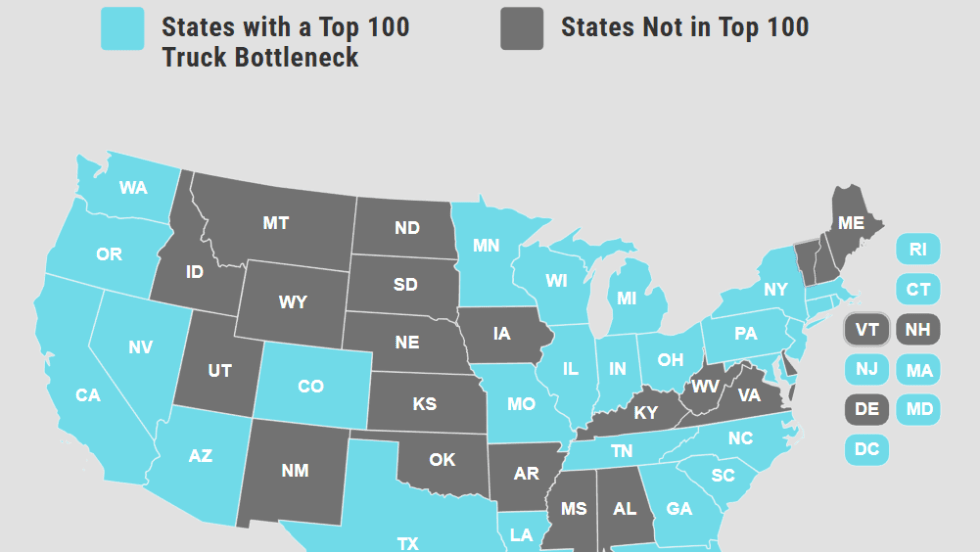

“It is certain that the energy patch will be hurt by this trade war, including states like North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas and Louisiana – as well as truck fleets that support those industries,” Meil said. “And that will have consequences for the U.S. economy overall, since that bright spot of economy activity could dim considerably.”

“A surge in oilfield activity was one of the reasons that the truck market was so hot in 2018, especially for flatbed,” Vise said. “If Saudi Arabia's price war makes it uneconomic for many oil exploration and production companies to remain in business, we could see oilfield activity drop sharply, which would hurt carriers involved in hauling frac sand, equipment, and so on. This would not be an immediate impact but rather one that could build through the year if crude prices remained low. One potential consequence is a drop in business for flatbed and specialized carriers, especially in the Permian Basin. However, a sharp drop in oil exploration and extraction has broader implications, such as less competition for drivers. This, too, is complicated. Carriers in all segments might find it a bit easier to get drivers, but that also could result in weaker utilization and softer rates. But this assumes we don't see broader effects on freight volume as a result of the ongoing coronavirus panic. If the current turmoil turns into a drop into a significant drop in freight, the eventual effects of low crude prices on utilization become largely beside the point.”

A final point Meil made is that lower oil prices could hurt North American truck sales, particularly the Class 8 market, which has also been cooling off since the end of last year. “One of the main selling points for new, long-haul, Class 8 tractors is the incredible fuel efficiency these new models get,” Meil says. “That 8-1/2 mpg average is a major inducement for fleets weighing new purchases. But if lower fuel prices are in play, it is possible some of those fleets will defer from making those purchases and continue to run older equipment.”

Both Meil and Vise stressed that it is far too early to predict how this new oil price war will play out – particularly given the volatility in the financial markets right now. Meil cautioned that the relatively calm business environment fleets have enjoyed since the 2008 market meltdown may be gone for the foreseeable future until some certainty and normalcy return.

“In the meantime, my advice for fleets is to prepare for market volatility in terms of both fuel pricing and business activity,” he said. “When you look at this oil price war in the context of an already-weakening economy and reduced activity/idle capacity in the transportation sector coupled with reduced manufacturing and retail activity, things look tough out there and fleets should plan accordingly.”