How does a self-driving truck get dispatched? What happens when it breaks down? If a receiver keeps it sitting waiting to unload? When it encounters a four-way stop or a policeman directing traffic? These questions and more were explored during a panel discussion at the McLeod Software 2018 User Conference.

How does a self-driving truck get dispatched? What happens when it breaks down? If a receiver keeps it sitting waiting to unload? When it encounters a four-way stop or a policeman directing traffic? These questions and more were explored during a panel discussion to explore the topic of smart trucks and autonomous vehicles during McLeod Software's 2018 User Conference in Birmingham, Alabama, Oct. 2.

Much has been made of how smart trucks are becoming. Today’s tractor-trailer is a computer – or in reality, many computers, fed by many more sensors and connected via telematics – rolling down the highway on 18 wheels. But as we progress toward increasing levels of vehicle autonomy, what’s the protocol for all that data interacting with real-world dispatch, routing, and back office software?

That’s the premise behind McLeod Software’s Smart Truck as a Client, or STAAC, initiative. It is building on the notion that a smart truck is simply another computer, or client, on the integrated information and data network of the supply chain.

Today, explained Brad Robinson, director of sales services for McLeod, there are numerous devices on a truck, some connected, some not. With the ELD mandate, more fleets are computerizing dispatch and using data for historical reporting and analytics. But how do you integrate the various proprietary systems? How does all that information get back and forth between the truck and the home office in real time?

“Imagine a landscape where the onboard computer is dispatching the load and productivity information to the driver, or the truck is sending maintenance and safety performance back to the home office, AI is analyzing it and maybe blockchain is recording it,” said Robinson. “STAAC lays the integration groundwork for the autonomous migration.”

Tom McLeod, president of McLeod software, said technology from mobile communications and telematics vendors has provided some incremental advances in this area, “but we’re not yet putting much computing and forecasting ability in the unit in the truck.” McLeod’s new driver app has added the ability to connect via APIs so drivers can see settlement information, send back images, etc., mostly information connected to the load.

“To make all the right decisions you’ve got to have all the right information, and there’s an enormous amount of information being gathered on the truck, on this STAAC,” McLeod said.

2 Phases of Smart Truck Automation

McLeod Software sees this migration happening in two phases.

With phase 1, the driver is still in the cab, but the truck is getting smarter every day. “This is where we can significantly upgrade the driver experience,” Robinson said, with incoming and outgoing data tracking and enabling things like platooning, truck parking, weather routing. The system could handle automatically rerouting a truck because of a road closed by a crash, taking hours of service and traffic into account, and even automatically notify the customer. And how about automated detention billing?

“A great deal of the software needed for this integration has already been built by McLeod and its partners,” he pointed out.

“What we see today, though, is some of the truck manufacturers and OEMs are just focusing on the autonomous truck — they’re looking at hardware and at safety, trying to keep it between the lines and keep from hitting another truck. What’s equally important are all these integrations and functionality, which are needed to transition into the phase 2 autonomous trucks. The key to STAAC is true systems integration.”

Phase 2, Robinson said, real autonomous vehicle technology, will involve new paradigms in command and control. Who manages the trip? Who schedules pickups? Who manages all these connected devices? Who manages disruptions? Who or what works to make the process more efficient? “STAAC provides the needed integration between tractor, driver, and home office to accomplish the autonomous tractor.”

Mark Cubine, McLeod vice president of marketing, pointed to the analogy of the military and its drone programs. They may take off under the control of the local air base in Kandahar, for instance, but switch to control in the U.S. for the actual mission, then back to local control for landing.

“What’s going to happen when the autonomous truck gets to the gate of the Walmart distribution center?” Cubine pointed out. “Do we still have detention problems? Who’s going to manage that part of the trip? My theory is you can detain an autonomous truck as easily as you can detain a driver right now, and that’s going to have to be solved.

“The assumption that [the autonomous truck] is going to be perfectly productive through the life of the trip is probably not going to be the way it’ll go.”

“We think the initial applications for autonomous vehicles may include long haul routes on an interstate, where the truck is accompanied by a driver up to the on ramp and travels by itself to the off ramp, where it picks up another driver,” explained Tom McLeod. “Information on those drivers will need to be connected to that load, and information on paying those drivers has to be connected to that load.”

That will require almost seamless access to the information from an operations center, he said, which today is the trucking company, and McLeod believes those relationships will continue rather than shippers turning to their own autonomous trucks en masse. “The truck becomes another client on the system with access to that information.”

For instance, he said, one of the simplest things is rerouting in case of real time traffic issues. “All the vendors putting real time routing on the vehicle are helping pave the way for more autonomous operation.”

Handling Breakdowns in Autonomous Trucks

One question related to the operation of autonomous trucks has been, what happens when something goes wrong mechanically with the truck on the road?

Matt Krump, director of connected services fleet health for Navistar, is part of the team that developed and launched OnCommand Connection in 2013, and spoke on the McLeod panel discussion.

OnCommand Connection is a remote diagnostics platform that works either through partner telematics companies or via International’s own integrated telematics device, on all makes of trucks, to provide fleet managers with comprehensive health reports on their vehicles. The system takes fault codes and translates them into English, including what symptoms the driver is likely experiencing to help confirm the diagnosis, and recommendations of what needs to be done next – does the driver need to pull off at the next exit? Get routed into the nearest dealer once he delivers his load? Or can it wait till the next PM?

This is the kind of information that will help make autonomous truck operation possible, Krump said.

As Cubine pointed out, right now, all too often fleet management doesn’t know there’s a problem with the truck until it breaks down, as drivers ignore warning lights in hopes of getting more paid miles under their wheels.

Krump said with today’s technology, such as OnCommand Connection, “other than running out of diesel, blowing a tire, or hitting a deer, you shouldn’t have unplanned downtime. And running out of diesel, shame on you, that shouldn’t happen. Hopefully in the future, tire management systems will help; it comes down to a deer, well...” Other than those few scenarios, he said, “we can turn unplanned breakdowns into planned downtime.”

With an autonomous truck, Krump said, it can be programmed to react in certain ways to certain situations, such as pulling off immediately for an emergency breakdown, or being routed to a service center that can fix the problem. Instead of depending on drivers who may ignore warning lights, “you can count on the vehicle is always going to follow that same command. It’s never going to have a bad day or not pay attention to something or ignore something.”

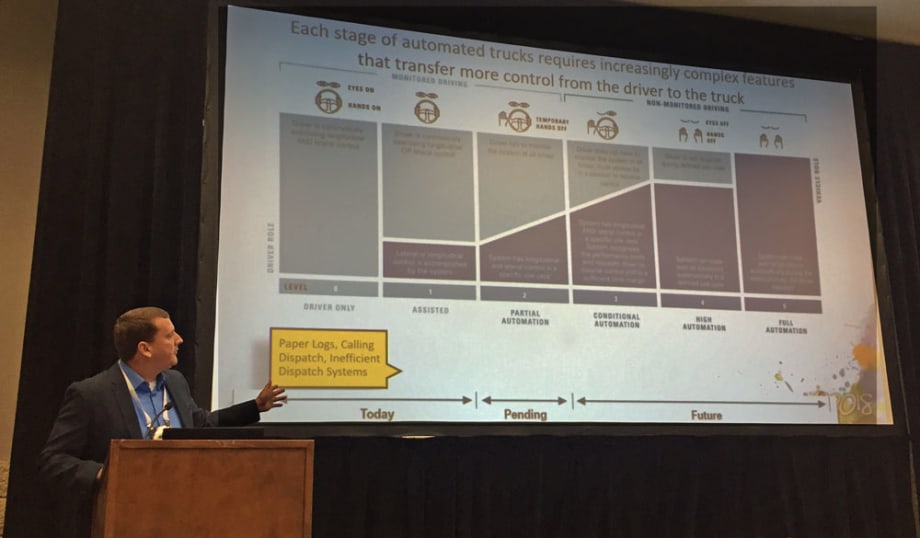

The Road to Autonomous Trucks

While the panelists were able to outline a lot of the challenges and solutions involved in making autonomous trucks a reality, they also acknowledged there are still a lot of roadblocks.

“You’re already seeing level 1 and level 2 [automation] right now,” Krump said. “It gets exponentially more difficult to move up each level. That level 5 [full autonomy] is significantly more difficult than level 4, for instance. So the timing of that is tough to predict. I think when we get to level 3 autonomy on vehicles coming off the line, we roughly predict about five years to get from level 3 to level 5 widespread implementation.”

He also pointed out that we won’t see the same level of automation implemented in all applications at the same time. “Those environments where you need the most human interactions are going to be the last places where level 5 is implemented,” he said.

For instance, Krump pointed out that autonomous vehicles are going to be programmed to follow the law. “But as a society we see a lot of examples of people operating a little outside the law, such as not coming to a complete stop, or going over the speed limit. How does an autonomous truck operate in that environment? What happens when you come to a four way intersection with an autonomous truck and it’s programmed not to move until all the other cars are stopped? That truck may be sitting there for quite a while. We’ve got to think of those things. How do we interact? When is it time for someone to remotely step in from home base, for the truck to call in and ask for help choosing the best path?”

He also cited as an example a situation where a police officer is manually directing traffic at a busy intersection where the traffic lights have gone out. “That officer is typically looking for eye contact. These are human elements that make it a little more tricky, and these will be some of the last areas for autonomy to be adapted. Drivers are here for the foreseeable future.”

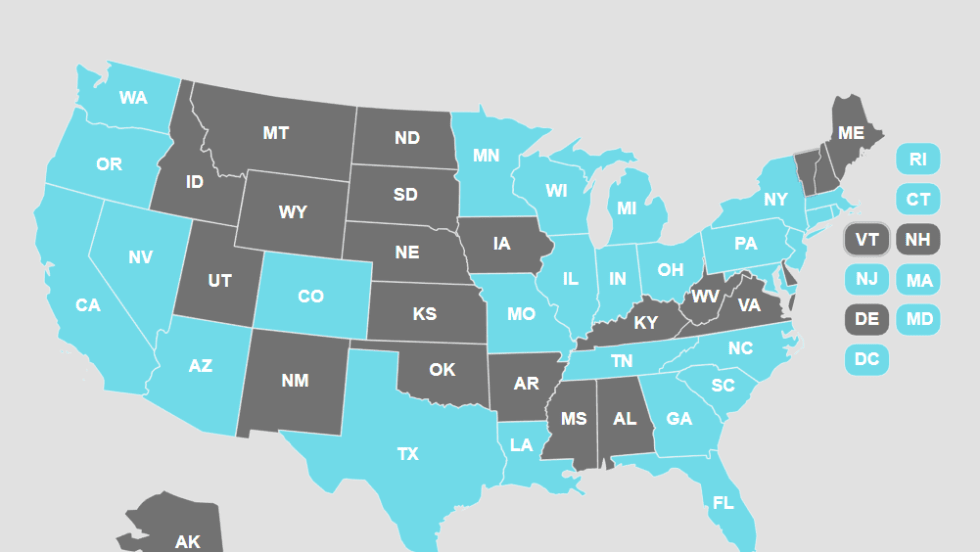

On the other hand, he said, we’ll see autonomous operations move ahead faster in “the safest places, like mile after mile of highway, or private roads, like mining – they’ve had autonomous vehicles running around mines for years. In our own factories going back years we’ve had robots moving parts from one part of the factory to the next.”

It’s also a societal question, he said, not just a technology one. “When will we have acceptance, when will regulatory bodies give approval, when will insurance companies back it? All those things have to fall in place.”