This one is different. The run-up is steeper and higher than diesel price spikes of the past. And the traditional supply-and-demand explanation - complicated enough by itself - has been muddied by unregulated commodity speculation. Everyone in trucking knows what it means at the pump right now, but no one can reliably predict where it will go.

The price history since 1994 climbs like the foothills of the Himalayas until last year, when it abruptly arrives at the base of Mt. Everest and turns upward with no summit in sight.

In April, ultra-low sulfur diesel was up almost 44 percent over April of last year, according to Energy Information Administration figures. Particularly shocking is the angle of ascent in the first quarter of this year: The price on May 5 was 24 percent higher than the price on December 31.

"Fuel is absolutely crippling this industry," says John White, executive vice president of U.S. Xpress Enterprises, echoing the sentiments of carriers across the country.

With diesel at more than $4 per gallon, and possibly more to come, the industry is looking at a reversal in its fundamental cost structure. In what used to be a labor-intensive industry, fuel is becoming the biggest expense, according to the American Trucking Associations.

"Over the past five years, total industry consumption of diesel fuel has gone up 15 percent, while the price of diesel has nearly tripled," Michael Card, president of Combined Transport, told the House Surface Transportation Subcommittee at a May hearing on diesel prices.

"The U.S. appears to be entering a period in which inexpensive diesel fuel has become a thing of the past," said industry analyst John Larkin of Stifel Nicolaus in a recent assessment of the fuel situation. "The price tag on each gallon of diesel fuel has succeeded in threatening the financial viability of many truckload carriers."

Less-than-truckload fleets also have been hit hard, Larkin said. "Fuel surcharges were not enough to make up for the added cost (of fuel in the first period of 2008), which had a negative effect on the carriers' operating ratios."

The impact probably has been hardest on small fleets and owner-operators that do not have the market presence or resources to pass on the price increases or absorb what their customers will not take.

Todd Spencer, executive vice president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, told the House transportation panel that one estimate has 935 trucking companies going out of business in the first three months of the year.

According to ATA, trucking failures among fleets with five or more trucks have been going up each quarter since the last period of 2006. There were more than 600 failures in the last period of 2007.

None but the foolhardy will predict where it's going to go. There are indications that it could get worse.

The president of OPEC, the international cartel that controls most of the world's oil reserves, has said that the price of crude could go up to $200 a barrel - up from $120 a barrel in April. Analysts at the investment bank Goldman Sachs seconded that assessment with their assertion that we are in a "super spike" that could reach $200 a barrel within the next two years.

On the other hand, some say prices will go down, if for no other reason than high prices eventually dampen demand among discretionary users. Adam Sieminski, chief energy economist for Deutsche Bank, put it this way: "We're engaged in a painful experiment in discovering how high the price has to go before it really, really hurts enough to slow demand globally." A Lehman Brothers analyst predicts oil prices could drop to $80 next year, in part because Saudi Arabia will release more production in an effort to curry favor with a new U.S. president.

There is a lot that trucking companies can do on the operational side to control fuel efficiency and purchasing, and industry lobbyists are pushing legislative measures that might ease some of the burden, but the fact is that the spike is occurring in the context of powerful economic and political pressures that are mostly beyond the scope of trucking's influence.

Closest to home is the national transportation infrastructure crisis: Government at all levels does not have the money to keep up with growing demand on the highways. There was little enough political will to raise more money by boosting fuel taxes before the price spike, and now some of the presidential candidates are going in the opposite direction by calling for a holiday from federal fuel taxes. Congress so far has shown no interest in that idea.

Meanwhile, the balance in the Highway Trust Fund is dwindling, and Congress is considering legislation to replenish it this year with $4.8 billion, most of which would come from general revenues. The long-term funding issue will come to a head next year, when Congress is due to update the law that governs federal transportation policy. Fuel taxes will be a hot issue in that debate.

Strong demand for oil, driven in part by growth in China, India and the Middle East, remains the major factor in global pricing. But the flow of investment money into securitized commodities is having a significant impact, according to a variety of sources.

"A huge portion of the run-up is attributed to the fall of the value of the dollar relative to other currencies," says Rich Moskowitz, vice president and regulatory affairs counsel of ATA. "Investment banks and hedge funds look at the retreating value of the dollar and want to take money out of dollars and put it into something more inflation-proof. If you look at most commodities since the beginning of the year, they have had double-digit growth, and oil has been no exception."

Dave Berry, vice president of Swift Transportation, believes that the price of crude oil has become disconnected from supply and demand. "The speculation that was in the housing market moved into commodities in general, and this is having a big impact on our prices," he said at Newport Communication's Economic Summit in Louisville, Ky., in March.

Not everyone agrees with this assessment. "Any apparent correlation between rising speculative activity and rising prices is a loose one at best," Guy Caruso, chief of the U.S. Energy Information Administration, told Congress late last year.

Ryan Todd, an oil analyst with Deutsche Bank, told the House Transportation Subcommittee that that speculation may exaggerate the price movement, but it did not create the run-up. "The problem with conspiracy theories or talk of price gouging is that it gives the oil companies far more control than they actually have," he said.

Sieminski of Deutsche Bank says there are five key factors behind the run-up and weights them as follows: 35 percent due to demand from China, India and the U.S.; 25 percent due to underinvestment in production and refining; 20 percent due to rising geopolitical risk, and 10 percent each to the falling dollar and speculation.

John Felmy, chief economist for the American Petroleum Institute, is in the same camp. He contends that tight supply and demand fundamentals are driving most of the run-up. He does not see oil inventories accumulating as he would expect if demand were artificially high due to speculation.

"Five economists will give you 10 opinions on this," he adds.

There is no equivocation, however, from the liberal activist group Public Citizen. "This era of high energy prices and record oil company profits isn't a simple case of supply and demand," Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen's Energy Program, told the House Transportation Subcommittee. "The evidence indicates that consolidation of energy industry infrastructure assets, combined with weak or non-existent regulatory oversight of energy trading markets, provides opportunity for energy companies and financial institutions to price-gouge Americans."

Congress has looked into the issue and found cause for concern. In 2006 the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations found that traditional supply and demand could not account for all of the price increases of that period. "The large purchases of crude oil futures contracts by speculators have, in effect, created an additional demand for oil, driving up the price of oil," the panel said in its report.

The solution, the panel said, is to restore Commodity Futures Trading Commission oversight over electronic commodity exchanges. Regulations governing that activity were loosened by the "Enron loophole" in a law passed in 2000.

Congress has legislation to close the loophole and add other measures that would strengthen regulation over aspects of commodities trading. A recent bill, for example, would increase the amount of money commodity traders have to put down when they buy oil futures. Right now the margin requirement is between 5 and 7 percent, which critics say makes it too easy for speculators to enter the market. There is plenty of opposition to these initiatives, so their passage is not a sure thing.

Trucking Initiatives On the Hill

The price run-up has revived congressional interest in legislation designed to ensure that fuel surcharges on truckload shipments are passed through to independent owner-operators.

"At OOIDA, we hear the stories every day of the drivers who have recently lost their businesses, and the overwhelming majority cite the inability to recoup increased fuel costs as the major contributor to their failures," Spencer said at the House Transportation Subcommittee hearing.

Spencer had a sympathetic ear in Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore. "It's only fair that when a shipper pays a fuel surcharge to a broker, carrier or independent driver that they are certain it's actually paying for fuel," he said. "I am confident that most brokers and carriers are honest operators that pass [through] any fuel surcharge to the person who purchases the gas. But there are bad actors out there."

DeFazio introduced the Trust in Reliable Understanding of Consumer Costs Act, or TRUCC, which would require carriers, brokers and freight forwarders of truckload freight that do not buy fuel for a shipment to reimburse the person who does buy the fuel. The payment would have to be accompanied by written disclosure of the amount of any surcharge collected by the intermediary.

The outlook for passage is not bright, due to opposition from other carrier interests, shippers and transportation intermediaries. These groups view the surcharge measure as a step back toward economic regulation of the business, and they question whether the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration has the resources to enforce it.

At the hearing, DeFazio pursued a line of inquiry that indicated he might be interested in an additional reform. He noted that some owner-operators say they have difficulty obtaining information about transactions among shippers, intermediaries and themselves, and said that this lack of information puts them at a disadvantage. Under current rules, he said, brokers and other intermediaries are required to keep records of transaction information - but what if they were required to send that information to owner-operators?

The idea ran into resistance from the Transportation Intermediaries Association. "We don't think it does anyone any good to know what the broker has negotiated as its margin with the shipper or the carrier," said Robert Voltmann, president and CEO of TIA.

Not all owner-operators are experiencing the same degree of difficulty noted by DeFazio. Ray Greer is president and CEO of Greatwide Logistics, a new and fast-growing non-asset-based transportation services company. "We have about 6,000 owner-operators and we have been able to secure fuel surcharges contractually," Greer said at the Newport Economic Summit. "Probably 60 percent of our business is passed through to the owner-operator directly, resulting in very little fuel issue for the company and therefore for them."

Greer cited Greatwide's aggressive use of on-board computers to monitor and control fuel consumption - a tactic that many progressive fleets are pursuing as fuel prices escalate. "The myth in the industry is that owner-operators would never adopt on-board technology, but we have found it to be widely accepted," he said. "That's because real-time monitoring of fuel consumption in the cab has resulted in $10,000 to $15,000 in incremental income right to their pockets."

The American Trucking Associations is pursuing a variety of legislative and executive actions in Washington to eke out price-related benefits for the industry.

It has called on President Bush to stop filling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and release some reserves in order to bring prices down. The government deposits 70,000 barrels a day into the 700-plus-million-barrel reserve.

"While we know that the SPR does not contain enough oil to permanently alter the supply of crude oil in the market place, we believe that strategic releases from the SPR could temporarily increase the supply of crude oil and hopefully help restore rational behavior to the petroleum markets," Michael Card of Combined Transport testified at the fuel hearing.

There is precedent for such a move - President Clinton opened the reserve during the price run-up in 2000 - but Bush has said he will not do so. The oil should be saved for emergencies, he said.

Also on the supply side, ATA is asking the Environmental Protection Agency to streamline the permitting processes for expanding and opening new oil refineries.

Card added that biodiesel quality still needs improvement, and Congress needs to take another look at the economics of that business. The $1 per gallon credit for biodiesel is set to expire next year, and in any event it does not cover the current cost of manufacturing that fuel, given the cost of the soybean feedstock.

Of particular concern to ATA is the practice of mixing biodiesel into an oceangoing tanker that is enroute to a foreign country in order to claim the tax credit. The "splash and dash" loophole is very bad tax policy, said ATA Senior Vice President Timothy Lynch.

And the association continues to press for a national diesel fuel standard to preempt the states from setting their own, "boutique" standards.

On the demand side, ATA is asking Congress to set a national speed limit of 65 mph and federal safety agencies to require speed limiters set at 68 mph. This comes as many fleets are slowing down their trucks - Swift Transportation, for example, has set its engine governors at 62 mph. "We did it because of $4 a gallon diesel fuel and we did it because of safety and we did it because of maintenance," Berry said. "We're hopeful that others will follow our example."

Congress has already passed a law designed to promote the use of auxiliary power units to reduce engine idling. The measure raises the federal weight limit by 400 pounds for trucks with APUs, so they won't be fined for being overweight. Trouble is, the Federal Highway Administration reads the law as discretionary rather than mandatory. So far, only seven states have passed laws recognizing the tolerance, although other states do use discretion in their enforcement. ATA is asking for a clarification.

ATA also is asking Congress to remove the 12 percent federal excise tax on idle reduction equipment, and is pushing for full funding for EPA's SmartWay Transport Partnership. SmartWay is a collaborative program that creates incentives for fleets to reduce fuel consumption - it aims to save between 3.3 and 6.6 billion gallons of diesel fuel a year by 2012. Funding has been cut recently, however, and ATA wants a line item appropriation to keep it going in the future.

Fuel Crisis Survival

Diesel price hikes take trucking into uncharted territory. Industry pushes for help on Capitol Hill.

More Fleet Management

DTNA Partners with Class8 to Expand Digital Services for Freightliner Owner-Operators

A new partnership brings free wireless ELD service plus load optimization and dispatch planning tools to fourth- and fifth-generation Freightliner Cascadia customers, with broader model availability planned through 2026.

Read More →

Reducing Fleet Downtime with Advanced Diagnostics

This white paper examines how advanced commercial vehicle diagnostics can significantly reduce fleet downtime as heavy duty vehicles become more complex. It shows how Autel’s CV diagnostic tools enable in-house troubleshooting, preventive maintenance, and faster repairs, helping fleets cut emissions-related downtime, reduce dealer dependence, and improve overall vehicle uptime and operating costs.

Read More →

Stop Watching Footage, Start Driving Results

6 intelligent dashcam tactics to improve safety and boost ROI

Read More →

Werner Expands Dedicated Fleet Nearly 50% With FirstFleet Acquisition

The $283 million acquisition of FirstFleet makes Werner the fifth-largest dedicated carrier and pushes more than half of its revenue into contract freight.

Read More →

Bobit Business Media Launches B2X Rewards Engagement Program

B2X Rewards is a new, gamified rewards program aimed at driving deeper engagement across BBM’s digital platforms, newsletters, events, and TheFleetSource.com.

Read More →

AI is Reshaping Trucking in 2026, from the Back Office to the Shop

Trucking’s biggest technology shifts in 2026 have one thing in common: artificial intelligence.

Read More →

Why Small Trucking Fleets Are Still Standing [Commentary]

Why discipline, relationships, and focus have mattered more than size for smaller trucking fleets during the freight recession.

Read More →

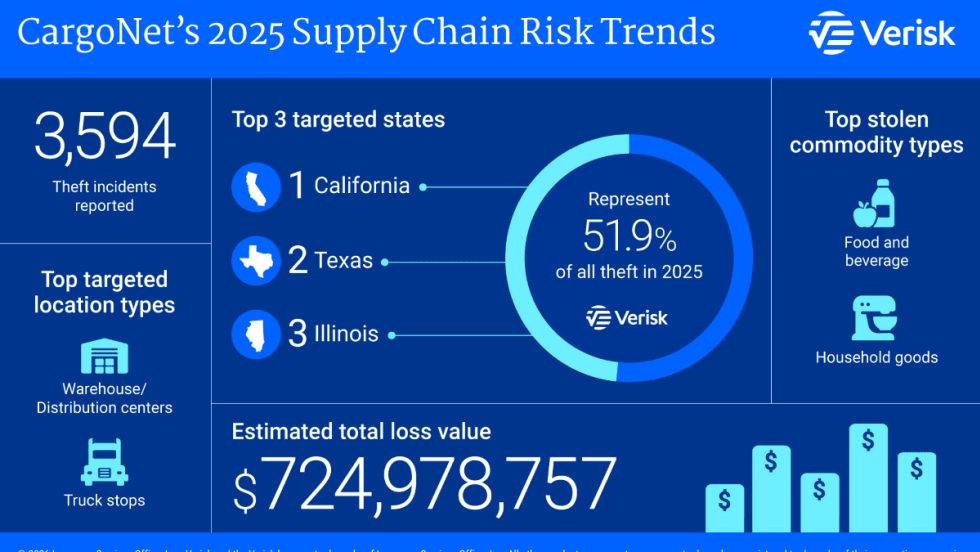

Cargo Theft Is Surging. A Bill in Congress Could Help. [Video]

Cargo theft losses hit $725 million last year. In this HDT Talks Trucking Short Take video, Scott Cornell explains how a bill moving in Congress could bring federal tracking, enforcement, and prosecutions to help address the problem.

Read More →

Cargo Theft Losses Jump 60% in 2025 as Criminals Target Higher-Value Freight

Cargo theft activity across North America held relatively steady in 2025 — but the financial damage did not, as ever-more-sophisticated organized criminal groups shifted their cargo theft focus to higher-value shipments.

Read More →

Phillips Connect, McLeod Integrate Smart Trailer Data into TMS Workflows

A new partnership between Phillips Connect and McLeod allows fleets to view trailer health, location, and cargo status inside the same McLeod workflows used for planning, dispatch, and execution.

Read More →