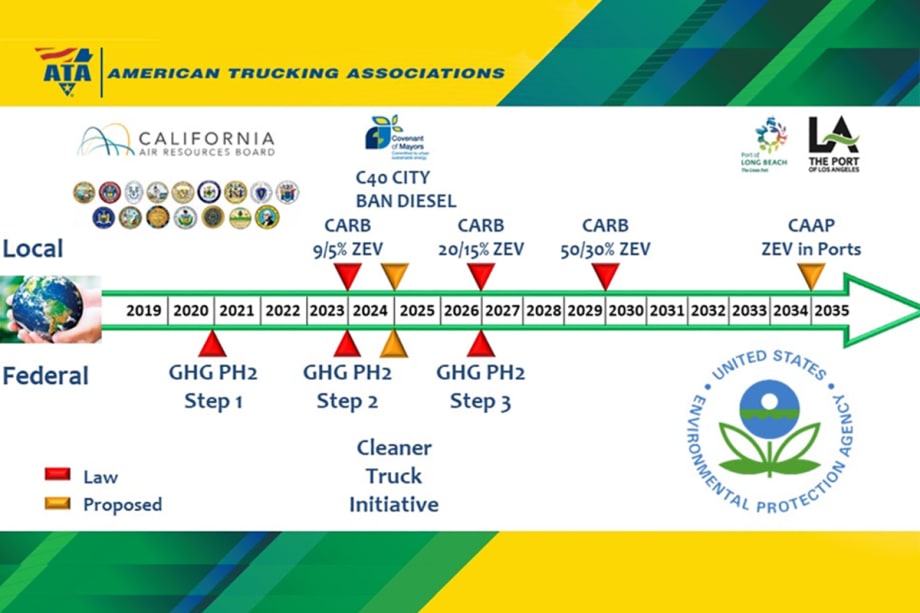

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the California Air Resources Board (CARB) are taking decidedly different paths to clean up truck emissions, leaving fleets with looming challenges including a new generation of equipment and even potential reporting requirements.

by John G. Smith, Today's Trucking

October 27, 2020The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the California Air Resources Board (CARB) are taking decidedly different paths to clean up truck emissions, leaving fleets with looming challenges including a new generation of equipment and even potential reporting requirements.

EPA has long set emissions limits for truck and engine manufacturers, but CARB plans even tighter rules than that – including steps that would require fleets to report their emissions every quarter, and stronger warranties for the equipment itself.

“It’s truly an unprecedented time in emissions regulations,” said Melina Kennedy, Cummins vice-president – product compliance and regulatory affairs, during an online panel discussion for the American Trucking Associations (ATA).

California has already finalized its Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) regulation that will require manufacturers to sell specific numbers of zero-emission vehicles beginning in 2024. By 2035 they are to account for 75% of Class 4-8 vehicles and 40% of Class 7-8 tractors.

This August, the state followed that by unveiling the final NOx emissions standards that take hold in 2024. NOx standards are expected to drop 75% in 2024, and then 90% by 2027. The U.S. EPA, meanwhile, is expected to finalize its latest emissions regulations in 2021, with a rule to become effective in 2027. It’s unknown if the emissions standards will align at that point.

Different Product Offerings

“Different standards will drive different product offerings between California and the rest of the U.S.,” Kennedy predicted.

California may not be entirely on its own, either. Fifteen states and the District of Columbia signed a memorandum of understanding in July, promising to collaborate on the adoption of zero-emission vehicles, with a goal of reaching 30% of medium- and heavy-duty trucks sales by 2030.

These jurisdictions collectively account for half the nation’s trucking economy, and 40% of the value of goods moved by trucks, said Steve Slesinski, Dana’s director – global product planning.

For equipment manufacturers, the California rules come with new test cycles and longer durability tests, as well as a state-specific bank for emissions credits, and requirements for longer warranties that would begin to take effect in 2022.

As promising as the longer warranties may sound, Knight-Swift senior vice-president – equipment and government relations Dave Williams stressed they’ll come at a price.

“The OEMs will have to end up passing those costs along,” Williams said. “We have to pay for it.”

Fleet Reporting Requirements

California’s proposal to require fleets to report on emissions is a “huge shift”, Williams added, noting that emissions-related compliance has traditionally fallen to manufacturers.

In late 2021, the Air Resources Board will decide whether to approve proposed vehicle reporting requirements that would begin in January 2023 under California’s state implementation plan, with enforcement coming only a few months later on July 1. Periodic testing requirements would come in 2024.

Model 2013 and newer engines would require data to be remotely uploaded, but pre-OBD vehicles would have to rely on third-party mobile testers, said Doug Powell, Kenworth’s director – fleet management.

The downloaded data could be collected by plugging a dongle into an OBD port, or automatically submitting the information through telematics. Geofencing, meanwhile, would track the trucks that come and go across state lines.

Williams is wary about the way data might be used.

“All of us fleets are starting to wake up to concerns about data in general,” Williams said. “Now we’re being asked to provide that to a state government …. We just don’t know what they’re going to do with that data.”

Tradeoffs for Emissions

There may be other tradeoffs in the process.

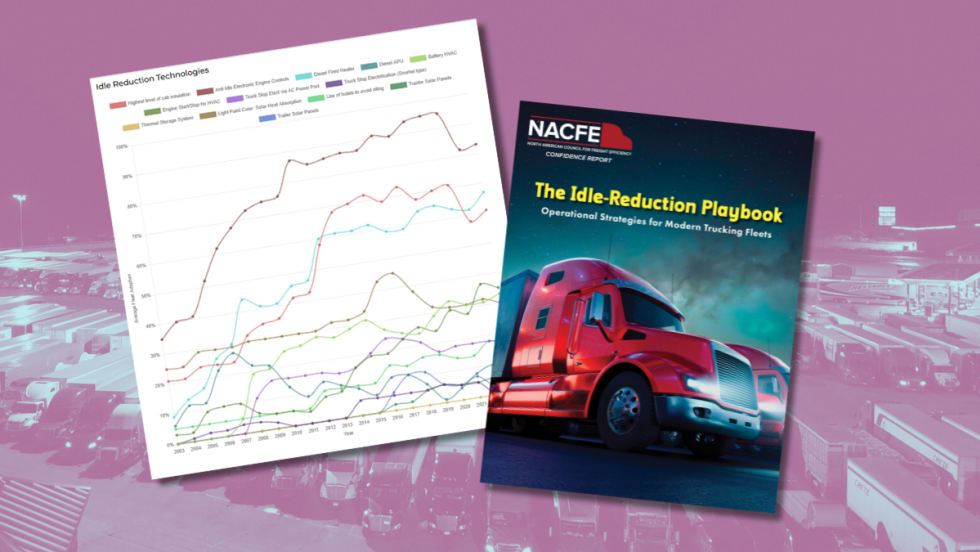

Changing emissions rules have always come at a cost. The first efforts to slash NOx came with exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), which lowered fuel economy, Williams said as an example. Some of that was recovered with the rollout of selective catalytic reduction (SCR).

Efforts to further lower NOx might involve more EGR or additional SCR, and maybe another technology altogether, he said.

“There’s a potential we see two different laws that may be fighting against each other.”

As promising as zero-emission vehicles appear, there are also limitations to consider.

“You have to recognize what they do and they don’t do,” Williams said, referring to challenges such as shorter ranges than diesel equipment, and the heavier weights. The added weights that come with battery-electric vehicles can easily surpass the 2,000-lb. allowances available in some states, he added.

“These trucks are not cheap – even with incentive monies. And these incentive monies are not going to be around forever,” he said.

“We’ve got to get this back somehow.”

The Cost of Emissions

Behind all the California-specific rules is the fact that trucks account for a significant share of the state’s emissions.

Heavy-duty vehicles are responsible for about 80% of smog-forming NOx emissions in California, half the GHG emissions when including fuel production, and 95% of the diesel particulate matter, said Slesinski.

It creates a health concern for those who live near ports, warehouses and freeways.

Zero-emission vehicles – running on batteries, fuel cells, or renewable natural gas — are seen as part of the solution.

California’s clean air regulations are expected to save 900 lives, avoid $1.7 billion in costs associated with CO2 emissions, and deliver $5.9 billion in industry savings, Slesinski noted. There’s also the promise of adding another $282 million to the state gross domestic product.

The changes may not be coming overnight, but he recommends that fleets should begin testing the related equipment today.

California’s zero-emission vehicle rollout begins with just 4,000 vehicles in 2024, but by 2030 it will involve 100,000 vehicles – between 30% and 50% of sales in the state. By 2035, the share will reach 300,000 vehicles.

“There’s other ways to get there besides electric energy,” Slesinski added, offering renewable natural gas as an example.

“One way or another we’re moving toward these zero-emission vehicles. The good news is it isn’t happening overnight.”

John G. Smith is the editorial director of Today's Trucking, where this article originally appeared. This content was used with permission from Newcom Media as part of a cooperative editorial agreement.