In 1986, the Chernobyl-4 nuclear reactor exploded, spewing molten core fragments and radiation. It killed more than 30 people and contaminated 400 square miles around the Ukrainian plant.

A "poor safety culture" was identified as a major factor. That was one of the first uses of the term.

Since then, "safety culture" has been used in industries such as nuclear power, manufacturing and aviation to describe safety as a shared value among all the people in company.

While the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administrations new Compliance, Safety, Accountability program, better known as CSA, is no Chernobyl, the new way of evaluating trucking companies has prompted many to take a closer look at safety and compliance. We spoke with several fleets about building a culture of safety and how CSA plays into that.

Several noted that safety and compliance are not always the same thing. Although CSA has prompted fleets to look at compliance differently, and it offers numerical targets to help with goal-setting, there have been questions about how well some of CSA's data truly affects crash reduction.

"There are a lot of things people do to be in technical compliance that have no real impact on their crash frequency," says Brian Kinsey, CEO of Brown Trucking in Litho-nia, Ga. "The fact that you have a perfect driver qualification file in nice neat order in a filing cabinet probably isn't going to impact whether or not that driver operates safely on the highway. Your qualification procedures and how he was dispatched that day have a much bigger impact."

Scott Randall, director of safety for St. Louis-based Hogan Inc., says at the end of the day, the discussion about regulations vs. safety is academic. Responsible companies work to both manage compliance and reduce crashes.

"Having a poor risk record is not only an issue of safety, it's an issue of good business," he says. Crashes not only cost money and downtime up front, they also can lead to lawsuits, higher insurance premiums and a company that's less attractive to shippers and brokers.

Hogan: Empowering drivers

Hogan offers dedicated, truck-load, expedited and third-party logistics services, as well as Hogan Truck Leasing, a NationaLease member. It runs about 1,200 tractors, mostly regional but some long-haul.

Missouri was one of the nine pilot states that tested CSA for about two years before it went national, so Hogan gained experience with it early.

One of the good things about CSA, Randall says, is that, for the first time, it measures individual drivers.

"Drivers can work with their carriers to help manage both the carrier's compliance record and the driver's individual performance record," he says. "It gives us the extra impetus we needed to get drivers on board. This isn't just an issue of policy or whether you work for us or not. This you carry with you, independent of what we do as a company."

CSA also "supercharged" his company's efforts to make operations staff realize they're also responsible for safety. It's about "getting operations to realize in a broader sense, that the needs of shippers, of customers, have to be balanced with and incorporate our responsibility as a safety-sensitive company."

At Hogan, safety and operations personnel jointly counsel drivers. At monthly meetings, safety, operations and maintenance personnel look at the company's current safety and compliance standings, what is working and what needs to be improved.

"Safety is a company-wide responsibility," Randall says. "Everybody has a stake in it. It's not just the safety department's responsibility."

One of the unusual things Hogan does is use a fatigue supervisor for overnight shifts. Drivers who are working between 11 p.m. to 5 p.m. are required to check in, and the supervisor follows up and contacts those who don't. Drivers who feel they are too tired to safely continue are encouraged to pull the truck over and call in to alert the company.

"It gives them a sense of empowerment, that ultimately you're in charge of the decision you make on whether and when to run," Randall says. That attitude transcends the question of fatigue. "The key is communication, drivers knowing they're not in this alone."

Drivers are given bonuses for clean inspections, but also held accountable if they're cited for something that should have been written up in a pre-trip or post-trip driver inspection.

Hogan is also a big proponent of the SMITH system of preventive driving. "Rather than talk about whether you caused it or someone else caused it, how about not having the accident in the first place," Randall says. "Don't become part of somebody else's accident."

Brown Trucking: Building relationships

Brown Trucking, a dedicated, regional and short-haul carrier headquartered in Lithonia, Ga., was started by a former truck driver who wasn't too crazy about the government telling him how to do his job. The company nevertheless had a very good crash frequency record, with better-than-average safety performance.

However, when the owner retired and sold the company, the new CEO Brian Kinsey saw CSA coming and "decided leaving it to chance wasn't good enough." He brought in someone to oversee the company's safety efforts, and Brown Trucking underwent a culture change between 2008 and 2010. (Brown was the pilot truckload carrier in Georgia's CSA pilot program.)

"Safety really isn't a driver problem," Kinsey explains. "It's a management problem."

It's important to make sure the people who have daily contact with drivers are well trained, aware of the rules and have a high level of empathy with drivers.

"We work on creating a personal relationship with every driver," he says. "A lot of it might seem hokey, but we have monthly safety themes and put posters everywhere," even bathroom stalls. Flyers about topics such as winterizing or driving around school buses go into driver mailboxes.

"Everyone knows A, we're a safety-first company, and B, if you want to stay here, you're going to behave a certain way."

Brown started honoring drivers who have a million safe miles working for the company, with a big ceremony, fancy dinner, leather lambskin embroidered jacket and other prizes. "They normally average 80,000 miles a year, so it takes 10 to 12 years to get to a million miles," Kinsey says. "To do that in primarily urban traffic without having a chargeable accident" is an achievement.

Kinsey says he has successfully worked on safety culture issues with previous employers - including a large owner-operator company where he was told he wouldn't be able to change anything because of the independents' mindset.

"That's absolutely not true," he says. "If you don't invest anything in making sure they have all the tools they need and are properly trained, you're not going to have a safe operation. If you do all those things, those drivers will be safer than your company drivers. It's their truck - they have more skin in the game." Brown is currently about half company drivers and half owner-operators. In both cases, he says, the key is the communication between them and the dispatcher.

"In some companies, there's never a relationship built up between that dispatcher and the driver," Kinsey says. "Our drivers are pretty open when they don't like something, and that's OK."

The company belongs to the Tennessee, Georgia and North Carolina state trucking associations, and has won the safety award for its mileage category in every one.

"We're not perfect," Kinsey says. "But I can tell you that our accident frequency has come down every single year, even as we grew the fleet by almost 150%."

A. Duie Pyle: Pulling in the same direction

A. Duie Pyle is a Northeast regional less-than-truckload, truck-load and warehousing and distribution company. In May 2011, the company brought in Dan Carrano as a dedicated director of CSA compliance.

Carrano had been in vehicle maintenance for 27 years before Pete Dannecker, director of loss prevention, brought him on to tackle CSA. His job was to help bring the safety department, maintenance department, operations and drivers together.

At previous employers, Carrano says, poor communication between the different groups meant separate teams that didn't always work together.

"At Pyle, everyone's pulling the cart in the same direction," he says. "They look at everything with a real broad perspective, and they don't just try to do everything right, they make every attempt to do everything right. The main thing is doing the right thing, not short-cutting anything when it comes to vehicle maintenance, driver pretrip inspections, hiring practices, training ... it all equates to safety."

Carrano worked to build relationships with drivers and technicians, worked with the safety department on enhancing driver orientation, and worked with drivers on pretrip inspections. He added driver accountability and mechanic accountability on doing pretrip inspections and making sure repairs were made properly.

One example was checking tires during the pre-trip inspection.

"It's easy for drivers to do what we call the inspection ballet, where they tap the tire with their foot, and that doesn't tell you anything," Carrano says. "We shared some of the tire costs with drivers, and asked them to think about the customer service impact if you're stuck on the side of the road. We educated them on tire life, on the impact that running a tire low on air does to the tire casing, and how it affects our fuel efficiency. We created posters where one of our drivers is pictured doing that little ballet, just to raise that awareness. I will tell you we felt it had some measurable result."

Dannecker notes that CSA has made it a little easier to get drivers on board as part of a culture of safety. "It gave us a better audience. Drivers are concerned about their own scores, so they're more alert and attentive."

Carrano analyzed information on breakdowns and roadside inspections to see if there was any fault on the driver or technician end, and used it as a learning opportunity to educate not just the person who was involved, but everyone who could have been involved.

Dannecker says the goal was to help people understand that what they do day-to-day is part of a much bigger picture that involves not only how well the equipment performs, but also equipment availability, the company's safety record, and how customers perceive the company.

Maverick: Technology as a tool

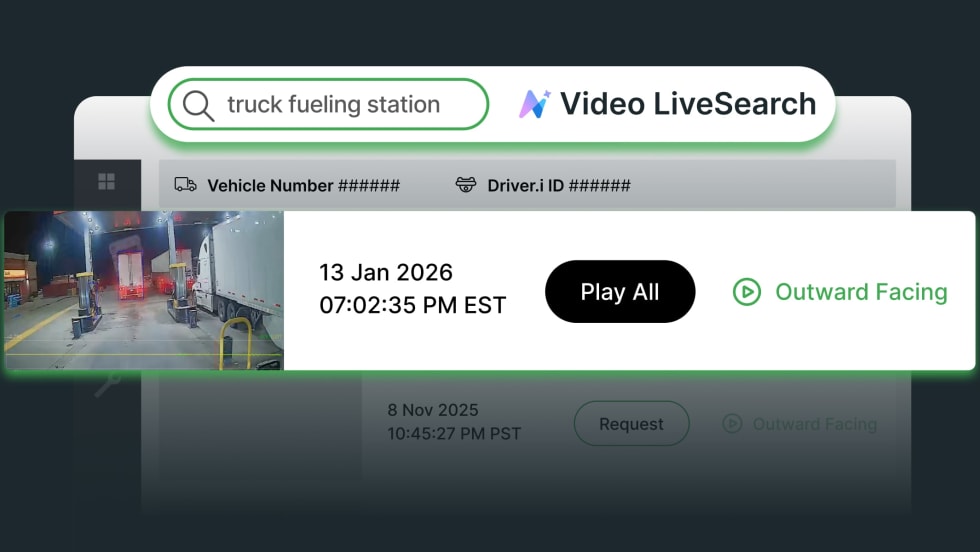

Technology plays a large role in safety efforts at Maverick Transportation in Little Rock, Ark., including lane departure warning systems, mobile communications, automated logging and predictive modeling.

But the technologies deployed "are part of our overall safety program and a part of our safety culture," says Dean Newell, vice president of safety and driver training.

In 1994, he recalls, one of the company's trucks had a wreck a few miles away from the main office. It was the first time the office staff had seen a wreck up close.

"The owner said, 'No more,'" Newell says. That was the beginning of Maverick's efforts to develop a safety culture. Now, everyone in the company has a safety plan, not just drivers.

Newell has been using predictive modeling from Qualcomm Enterprise Service's Fleet Risk Advisors business unit for three or four years. He says the modeling can tell them what's going on in a driver's life by picking out patterns. "It allows us to focus on guys we would not have focused on."

If a driver has been working for a company for a number of years without an accident and then one day he makes a right turn and hits a pole, "he didn't suddenly forget how to drive," Newell says. Instead, there are probably things going on in that driver's life that have an impact on his or her driving.

"You can't control what's going on in a driver's life," but predictive modeling helps identify those drivers. Newell describes predictive modeling as an active system, rather than a passive system. It identifies drivers that need more coaching before there is an incident.

The model identifies the 10% of the company's 1,350 drivers most likely to have an accident within the next 28 days. Based on this information, Newell has a conversation with these drivers.

"I just ask them how they are doing," he says. "When you ask them, they will open up and we let them guide us down the path of what they want to talk about. We don't say anything about the model."

Drivers targeted for this type of remediation are identified by predictive elements in the model that one would not normally associate with safety risk. "It could be shift start variations or an enormous amount of Qualcomm or email messages."

As a vice president in charge of safety, Newell says he uses the various technologies, driver coaching and driver recognition as tools in the company's overall safety program. "But you can't just put technology on a truck and be done with it; you have to work with it. It's about changing behavior."

It is also about adhering to a safety culture, where safety is a value and not just a priority, he explains.

"Priorities change from day to day. Values don't. That's why we make safety a value."

From the October 2012 issue of Heavy Duty Trucking magazine.