NMFTA Targets Freight Fraud and Telematics Supply Chain Risks

New carrier identity checks, industry resources, and telematics supply chain research aim to make freight fraud and cyber risks harder to exploit.

Read More →

New carrier identity checks, industry resources, and telematics supply chain research aim to make freight fraud and cyber risks harder to exploit.

Read More →

Fleet software is getting more sophisticated and effective than ever, tying big data models together to transform maintenance, safety, and the value of your existing tech stack. Fleet technology upgrades are undoubtedly an investment, but updated technology can offer a much higher return. Read how upgrading your fleet technology can increase the return on your investment.

Read More →

Company consolidates Bestpass, Drivewyze and CPSuite into one platform aimed at reducing vendor complexity and controlling fleet costs

Read More →

Cargo theft has evolved from parking-lot break-ins to cyber-enabled strategic fraud. Here’s what fleets need to know.

Read More →

Cargo theft has shifted from parking-lot break-ins to organized international schemes using double brokering, phishing, and even spoofing tracking signals. In this HDT Talks Trucking video podcast episode, cargo-theft investigator Scott Cornell explains what’s changed and what fleets need to do now.

Read More →

Daimler Truck’s David Carson sees early signs of tightening capacity — yet buyers remain wary, extending trade cycles and resisting a pre-2027 emissions surge.

Read More →

The American Transportation Research Institute's annual analysis of truck speeds through congested interchanges yielded a new worst bottleneck this year.

Read More →

From pricing intelligence and compliance tools to charging infrastructure, diagnostics, tires, and AI, HDT’s 2026 Top 20 Products recognize the new tools, technologies, and ideas heavy-duty trucking fleets are using to run their businesses.

Read More →

Disasters don’t wait — and fleet operations can’t afford to either. The 2026 Disaster Response Guide is now accepting expert insights on preparedness, response, and recovery strategies.

Read More →

Artificial intelligence is evolving faster than fleets can keep up, and telematics must evolve with it, Cawse said during Geotab Connect. The future? A single AI coordinating every system — and leaders who know how to guide it.

Read More →

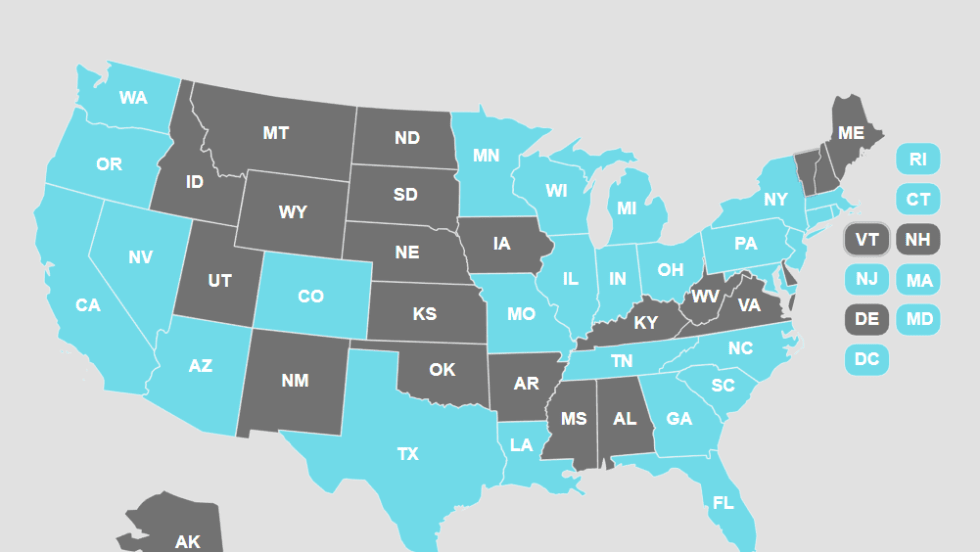

Survey data show carriers and brokers expect improving demand in 2026, even as rates lag and capital investment remains on hold.

Read More →